The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art is a new release, edited by Jeffrey Ian Ross, which aims to be a comprehensive reference on the subject. At nearly five-hundred pages the book is pretty mega with contributions from a whole range of experts on a number of different topics. Inside there are thirty-five chapters that are split into four key areas. The first is a look at the different types of graffiti, some historical, and what their meanings are. After is a section that focuses on the theory behind the study of graffiti and street art. This is followed up with examples of different place specific graffiti and finally seven chapters around what effect graffiti has on areas such as policy, culture, or mainstream art. As there’s just so much content in the book it’s been a bit hard to work out where to begin. I was particularly interested by certain themes that kept cropping up through the book so decided to focus on a couple of them. The first of these is how discussion of graffiti, more often than not, revolves around issues of contested urban space, state control and gentrification. Graffiti is closely tied up with the effects of neoliberalism which is discussed a lot in the book. Another interesting topic is female participation and the role of gender within the graffiti subculture. After this I dip into two of the chapters from the theory section and then end by briefly outlining a few other chapters to give a better idea of the range of content. As already mentioned this book is pretty thorough and what’s covered here is only a small sample of that.

In a scene at the beginning of Adam Curtis’ recent documentary, HyperNormalisation, the artist Patti Smith is shown travelling through New York in the 1970’s. As the camera sweeps over a wall of graffiti she comments “look at that. Isn’t that cool? I love that, where, like, kids write all over the walls. That, to me, is neater than any art sometimes.” The scene highlights how, as neoliberalism took hold of New York, many people had become disillusioned with politics and retreated into an individualist radicalism that sought transformation through self expression rather than collective action. Instead of trying to change the city around them “they just experienced it.” In fact the graffiti Patti Smith points out was itself both a demonstration of this new individualism and a product of neoliberal policies. In his forward to the Routledge Handbook Jeff Ferrell links graffiti, what he calls “the most publicly visible forms of contemporary urban culture”, with the current effects of neoliberalism. Increasing state control, gentrification and consumerism are all effecting modern urban space; how it’s built, used, and experienced. Ferrell points out that graffiti is a contradictory marker of this in that it is a “signifier of new urbanism” yet a challenge to it too. This sort of contradiction is a reminder that understanding graffiti, in all its different forms and contexts, is always going to be complex.

Increasing state control, gentrification and consumerism are all effecting modern urban space

Doreen Piano’s chapter on post-Katrina New Orleans highlights some of these complicated dynamics in a recovering city. It has been argued that the 2005 hurricane was deliberately used as an opportunity to push neoliberal policies by reshaping urban spaces and privatising public services. Meanwhile there has been a renewed presence of graffiti in the city and the responses to it feed into questions over who controls New Orleans and its image. Piano describes some of this graffiti beginning with the immediate aftermath when residents wrote all sorts of messages on the walls. These ranged from the humorous to the defiant, warnings to would be looters, personal messages, and political ones aimed at the authorities. Local writers soon began to make their mark as well. Some of them used the language of destruction in their writing (ie Harsh, Evak and Risk) and their tags were read as reflections of it. International street-artists, such as Banksy, also came to make their mark and put New Orleans on the international street art map. Some have viewed all this graffiti and street art as a positive element in the city’s recovery which empowered residents, beautified their space, and even gave it an economic boost. Piano also suggests that local culture, such as a tradition of ‘custom lettered signage’, meant residents were more receptive to the graffiti. However local government policy often sought to control the use of public space. Street bands and clubs were targeted with fines and new anti-graffiti policies were put into place. A local ‘tinpot lawman‘ known as the Gray Ghost, who formed a non-profit group to eradicate graffiti, was effectively sanctioned by the authorities.

New Orleans is just one example of the politicised tussle over control of visual space within modern cities. Similar themes are raised in other chapters within the book from Paris and Tokyo to revolutionary Egypt. In an engaging chapter, titled ‘New York City’s moral panic over graffiti’, Ronald Kramer explains how graffiti was originally politicised and a vision created of it “as a monolithic destructive force” that has since spread as a useful ‘moral panic’ tool for governments. The creation of this moral panic was a convenient diversion as neoliberalism caused massive economic hardship to the New York that Patti Smith observed. While her contemporaries became more atomised, the state also created a mantra of ‘personal responsibility’. Now individuals were responsible for their own poverty and misfortune. The state increasingly “supported punitive responses to deviance and those who fail to display docility.” Kramer argues that the moral panic over graffiti wasn’t just a political sideshow but also a covert way of introducing and legitimising draconian laws against those in poverty.

In his piece Kramer also discusses the militarisation of the state’s reaction to graffiti in New York. As a moral panic relies on an exaggerated narrative it also results in disproportionate responses. Excessive resources have been put into policing, while the transport authority has even sought advice on anti-graffiti ‘weapons’ from NASA. For Nancy Macdonald this onslaught takes on a different dimension as a “militaristic world of machismo” that “is warfare in writers’ minds.” She claims that male graffers actually welcome this ‘war’ as a means of constructing masculinity. Early on in the book Susan Phillips mentions, in relation to gang graffiti, that the role of gender is understudied. However the Routledge Handbook does include chapters that pay attention to this issue directly. Macdonald is the author of a book called The Graffiti Subculture which explored how graffiti culture was a way for young men to form a masculine identity whilst excluding women. In the Routledge Handbook she says that, since writing her book, both the rise of street art and the internet have been catalysts for a radical change in womens participation in graffiti and street art. In the chapter ‘Ways of being seen’ by Jessica Pabón several of these active female graffers and street artists are discussed. How these writers choose to project their gender is often central to their tag, style, and methods. For example Free was the first female to paint pixação in São Paulo. She chose her tag to represent her defiance against patriarchal society but at the same time it was a neutral name that initially hid her gender as she gained respect as a pixador. In contrast Ivey uses feminine symbols to create a style that clearly states her gender and forces the viewer to acknowledge her identity. Other women collaborate in all-female crews as a way of creating their graffiti. Women on Walls is an Egyptian collective who use graffiti as their medium of political expression to challenge sexism and misogyny. Pabón concludes that, through a range of methods, women are not only changing the graffiti aesthetic itself but “the sexist and bigoted generalizations about the graffiti/street art ‘doer’” too.

Two other interesting, but very different, examples of gender playing a role in graffiti production and consumption deserve a mention here too. The first of these, by Adam Trahan, focuses on graffiti found in toilets (termed latrinalia) and, as these are rooms divided by gender, he goes into a discussion of the differences between male and female graffiti. He suggests that, alongside its anonymity, this division means that latrinalia is a unique “source of intra-gender discourse and identity”. The second of these chapters is called ‘Yarn bombing – the softer side of street art’. My immediate thought when I saw the title was “that’s not graffiti!” Presumably this chapter is included as graffiti and yarn bombing are both covered by the umbrella terms urban or street art. The author Minna Haveri introduces knitting as a predominantly female craft that hasn’t been valued as much as the ‘arts’ which have traditionally been dominated by men. More recently crafts, such as knitting, have slowly come to be appreciated as art in their own right. Starting in 2005 a new form of street art emerged whereby knitted pieces were displayed in the street. This new ‘yarn bombing’ soon spread with the help of the internet, and became a way to interact with the urban environment. Haveri says that the new craft movement is a creative outlet that can be political and subversive at times. Yarn bombing in particular is about “positive activism” which Haveri, oddly, contrasts with direct action and anarchism. At times the subject of yarn bombing becomes slightly twee. One London based group choose not to engage with the term ‘bombing’ because it could be deemed offensive in a city that has been shaped, physically and culturally, by real bombs. Another of the yarn bombers discussed is almost objectionable in how they relate to public space. Olek, held up as a renowned yarn installation artist, seems to view the city as a playground for her art gallery chums and declares “I don’t yarn bomb, I make art”. Aside from this, Haveri’s description around the role of crafts and knitting is interesting and, actually, the link with graffiti has been made elsewhere. In issue 10 of the Swedish graff magazine Kilroy graffiti is described as a modern craft. In the article ‘Craft and Graffiti’ traditional folk art is compared to graffiti while the text is illustrated with a picture of a group of women knitting.

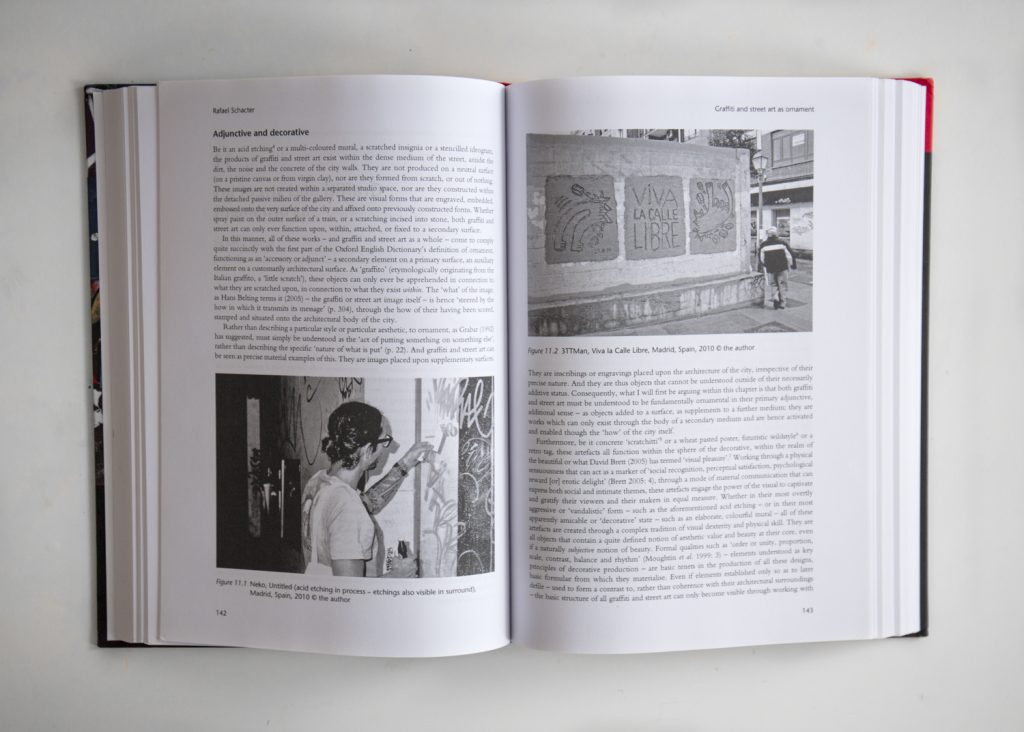

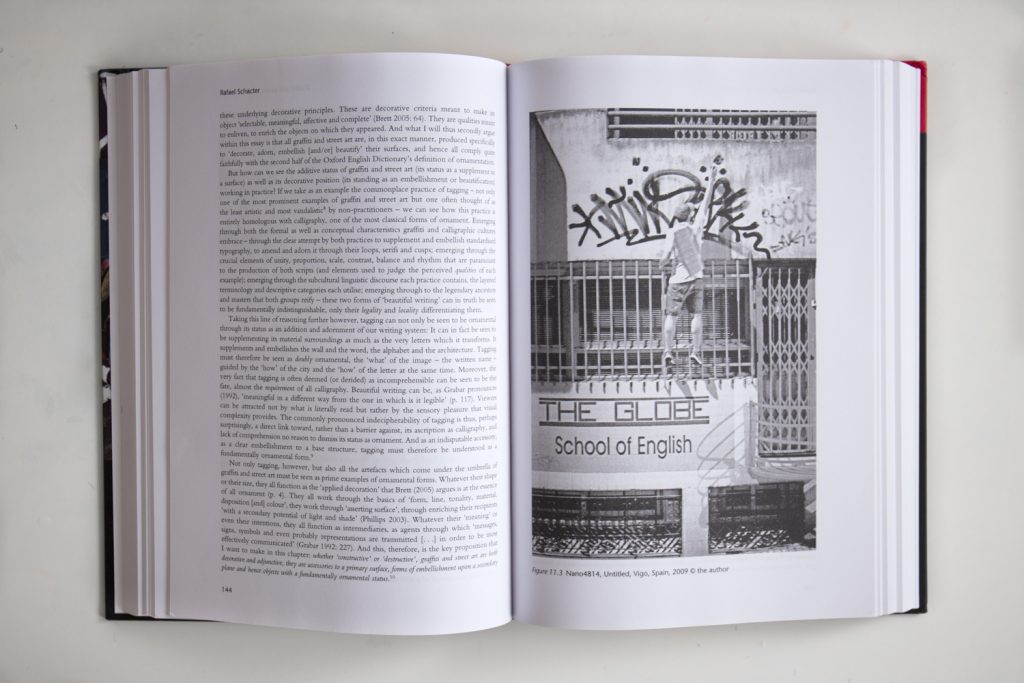

One way that the complexity of graffiti and street art can be approached is by framing new theoretical accounts of it. Rafael Schacter tries to break away from the standard dichotomy of graffiti as legal/illegal or art/vandalism. Instead of a simplistic, good or bad, understanding of graffiti Schacter introduces a concept of graffiti as ‘ornamental’. By putting graffiti on a wall the graffer is adding a new layer of material to the surface of the building. So in this sense a piece of graffiti is literally an ornament placed on the architecture of the city and can only be understood as part of the surface it is on. Schacter argues that wether graffiti is viewed positively or not the fact that it’s ornamental means that it becomes decorative art. He compares tagging to calligraphy and says that in fact the tag has two ornamental functions in that it ornaments the ‘writing system’ as well as the surface it is placed on. Just like a column on a museum, or a door number, such ornaments are integral to the architecture they are placed on. The argument here is essentially that buildings require graffiti. While it ornaments, graffiti also disrupts the image of buildings that are used as monuments to convey power and dominant ideas. The presence of graffiti and street art becomes threatening as “a non-institutional practice” that publicly subverts and questions. Schacter argues that ornaments, such as graffiti, “act as material indicators of their producer’s agency.” This idea can be illustrated with examples from some other chapters in the book. When Macdonald argues that the tag isn’t just a ‘creative product’ but “the display of (its) perceived masculine qualities” she demonstrates how the viewer is concerned with the author as much as the writing itself. Another example could be taken from the chapter on yarn bombing where Haveri highlights how the practice is often questioned, as the product could be put to ‘better’ practical use. Is such criticism always about concern over resources or over the role of the producer? When the viewer perceives the producer of an ornament to be a threat they denigrate it not because, for example, a tag itself is threatening but because the person who put it there is. Both Kramer and Susan Phillips emphasise the resulting dehumanising discourse that commonly equates taggers with animals, such as dogs marking their territory. Here Schacter’s explanation of graffiti as ornamental provides a more nuanced approach to studying graffiti. One which doesn’t rely on an opinionated and overly simple, positive or negative, judgement as its starting point.

Similarly Andrea Brighenti also wants to get beyond over simplified assumptions and introduces the term ‘place valorisation’ to try and get a better understanding of graffiti’s contradictions. This is the idea that street art and graffiti give value to places. However graffiti is only ever visual and ephemeral so while it can give value, a value can’t necessarily be given to it. Also the value of any commodity isn’t scientifically ascertained but comes about through a variety of human factors. Despite street art often being viewed in a positive way Brighenti argues that the illegal aspect of graffiti is inseparable from it. While legal street art is commodified it relies on the illicit image of graffiti for it’s authenticity. As an example he quotes Insa who, despite his work being commissioned by multinational fashion brands, says that his art challenges consumerism. Brighenti suggests that this claim can only be made because legitimate artists like Insa rely on the illegal ‘authenticity’ of graffiti. Gritty urban chic is a sought after appearance that can give a supposedly run-down area a vibrant and attractive identity for developers to sell. Even though the graffiti doesn’t necessarily remain in gentrified areas its value does. Graeme Evans, in his chapter, talks about Hackney Wick which is a prime example of this. Hackney Wick is a formerly working class area of London that is going through a process of gentrification and the graffiti found there has contributed to its cool image. In the run up to the 2012 Olympics the authorities covered much of the local graffiti and street art over. However they also used Hackney Wick’s reputation to commission works by international street artists in the area. Through place valorisation theory Brighenti wants to show that even when graffiti is viewed negatively it can still give value to a place. He says that graffiti and street art are not simply being appropriated by the establishment but rather are being integrated and rejected at the same time.

Banksy is mentioned in almost every chapter but, while it would be hard to overstate just how influential he has been on the public’s imagination, he is just one amongst many others.

Moving on from the theoretical I’ll briefly mention a few other chapters in the Routledge Handbook that I enjoyed reading. A couple of the more unusual topics, that are also related, are hobo and gang graffiti. John Lennon describes graffiti made by itinerant hobos who hopped the US railways to find work across the country. He shows that much of what is commonly perceived to be graffiti created by hobos on freight trains was actually done by the railway workers themselves. While these workers were tied to one locality their graffiti travelled across the continent. By contrast hobos who made graffiti travelled around with it and even competed with other hobos. Lennon also refutes the idea that this sort of graffiti was commonly used as a secret language. Instead he says that this early freight train graffiti was a way for marginalised working class people to leave their mark on the railways that were so important to their lives. Interestingly hobo graffiti was an early influence on american gangs who used tar collected from freight trains to leave their mark. Phillips works on deconstructing gang graffiti and challenging common misconceptions about it. In two case studies she breaks down pieces of gang graffiti to show the meanings they contain. Territory, affiliation, and rivalries are symbolised through numbers, crossed out letters, and abbreviated names. Phillips contests the assumption that gang graffiti leads to gang violence, and points to another study that found the clean lettering styles of gang graffiti countered the disordered environments they were produced in. These gang styles, such as cholo, have crossed over into mainstream graffiti which Phillips says has resulted in a focus on gang style rather than social context.

When talking about Native American graffiti Favian Martín also talks about the gangs who create graffiti in those communities. Contrary to Phillips he asserts that gang graffiti does create gang violence. On many reservations the fear over an increase in gang activity has led to the sort of zero tolerance policies that Phillips argues are draconian and based on inaccurate assumptions. However not all graffiti made by Native Americans is considered threatening. In fact some of it is seen as empowering for the community when it is used as a way of publicising political and social problems. Martín writes about the two year long occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969 by Native American activists who daubed messages on several of the buildings while they were there. Some of this graffiti has since been preserved by the National Park Service. This example is quite interesting as it demonstrates just how context dependent readings of graffiti are, and how culturally sensitive graffiti is. In another instance graffiti left on National Park land by the writer Creepytings led to a public outcry, she was prosecuted, and her work was removed. The difference in these reactions to graffiti highlight particular attitudes towards public space and who it belongs to. Evans argues that, like the Alcatraz slogans, graffiti continues to be a counter-hegemonic activity and one that is now a “global cultural force”.

Before I wrap up I will mention the few criticisms I have of the Routledge Handbook. As there are contributions from dozens of different authors it sometimes seems that relevant ideas expressed by one aren’t addressed by another. For instance, when discussing policing tactics, neither Macdonald nor Kramer discuss each other’s arguments. So while Kramer doesn’t really acknowledge how the graffiti culture itself reacts to policing, on the other hand Macdonald suggests that authoritarian policing is welcomed by graffiti artists! In another example Evans says “that while there appears to be a softening of policy and responses towards graffiti, this does not mean there is less governance (of it)”. However Kramer doesn’t mention this changing dynamic at all. Elsewhere several chapters in the book discuss the role of the internet and it would have been interesting to have a dedicated chapter on the topic. The effect of the internet seems to be particularly important when considering growing female participation in contemporary graffiti and more widely street art dissemination. The internet is also important for research; Piano says that instagram is now an essential tool for graffiti study, while in Mona Abaza’s chapter on Egypt over 70% of the listed references are from the internet. Perhaps a drawback of using the internet like this is that it favours particular actors in a culture that can be secretive to the point of paranoia. Banksy is mentioned in almost every chapter but, while it would be hard to overstate just how influential he has been on the public’s imagination, he is just one amongst many others. A possible solution to this, as Ross points out in the introduction, could be through researchers spending more time with actual street artists and graffiti writers. Finally, my major criticism of the Routledge Handbook is simply the price. The book is mainly aimed at students and academics, which is occasionally borne out with the mention of ‘polymorphous magical substances’ or use of the word ‘purview‘. To be fair the book avoids too much overly-academic language and Ross does say that he intends the book to appeal “to a wide international audience”. Unfortunately it’s just so expensive that, unless they have access to a really good library, most people will probably not be able to read it. Which is a real pity as this is the go-to handbook for anyone interested in graffiti.

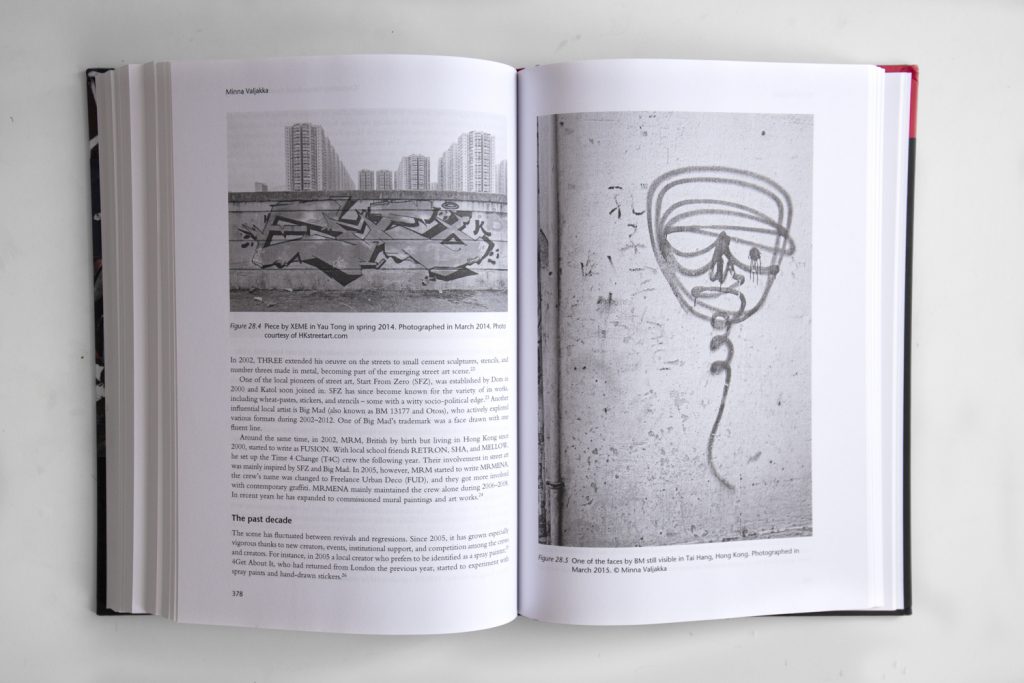

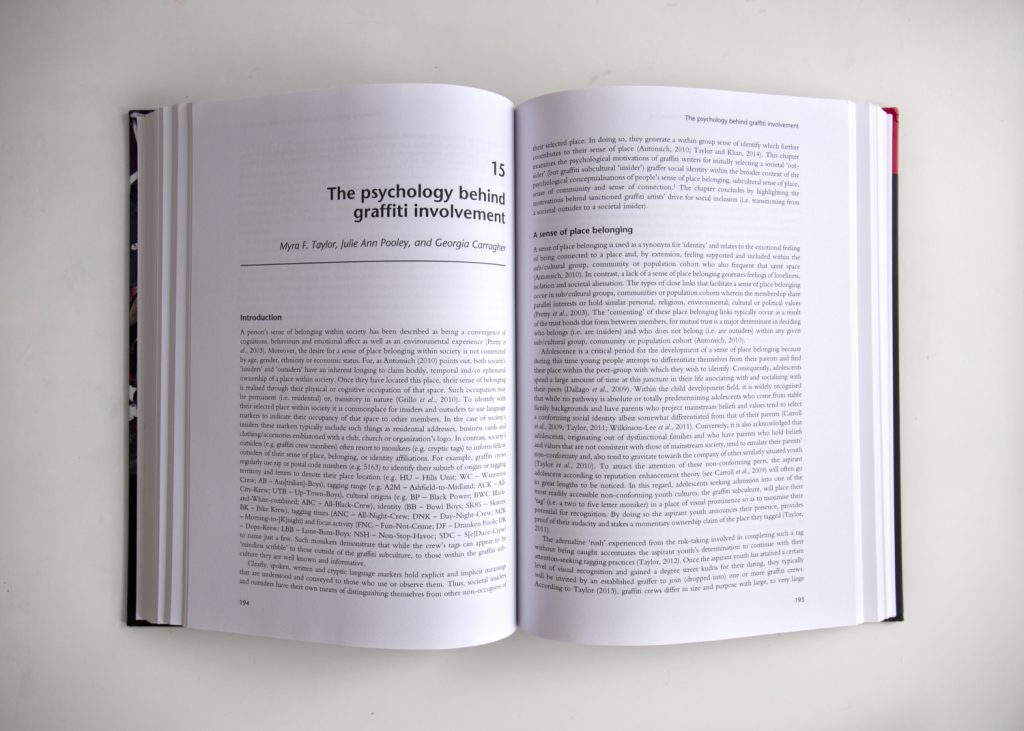

Overall the Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art is a fantastic book. There is a large and diverse range of topics from graffiti on screen, or prison walls, the psychology behind it, ancient graffiti, South American political murals, graffiti as career, the history of freights, the Far East, to legal writers, and the street art which Pabón says itself descended from hip hop graff. It is the particular focus on contemporary graffiti, which spread from New York in the 1970’s, that is really positive. Quite often fairly tenuous links are made between wall writing traditions across history to modern times but here both the broader and more direct links are put across well. Graffiti needs be considered within its locality and context and in this the ‘regional’ section worked well. Having the four key areas helps keep the book manageable when there is a lot of information to get through. There are plenty of photos and all sorts of interesting nuggets of information to be found. While it looks a bit daunting overall the book is easy to read and definitely gets the thumbs up!

Pingback: 100% Straße – Graffiti Review

Great review. The author has written about terrorism and prisons as well. Sounds like an interesting read.

This is a great thorough review and thanks for going into details about my contribution. I agree about the price and the criticisms of not paying enough attention to the Internet both as a research site and as an extension of urban space that gives some graffiti and street artists a celebrity status while excluding others.