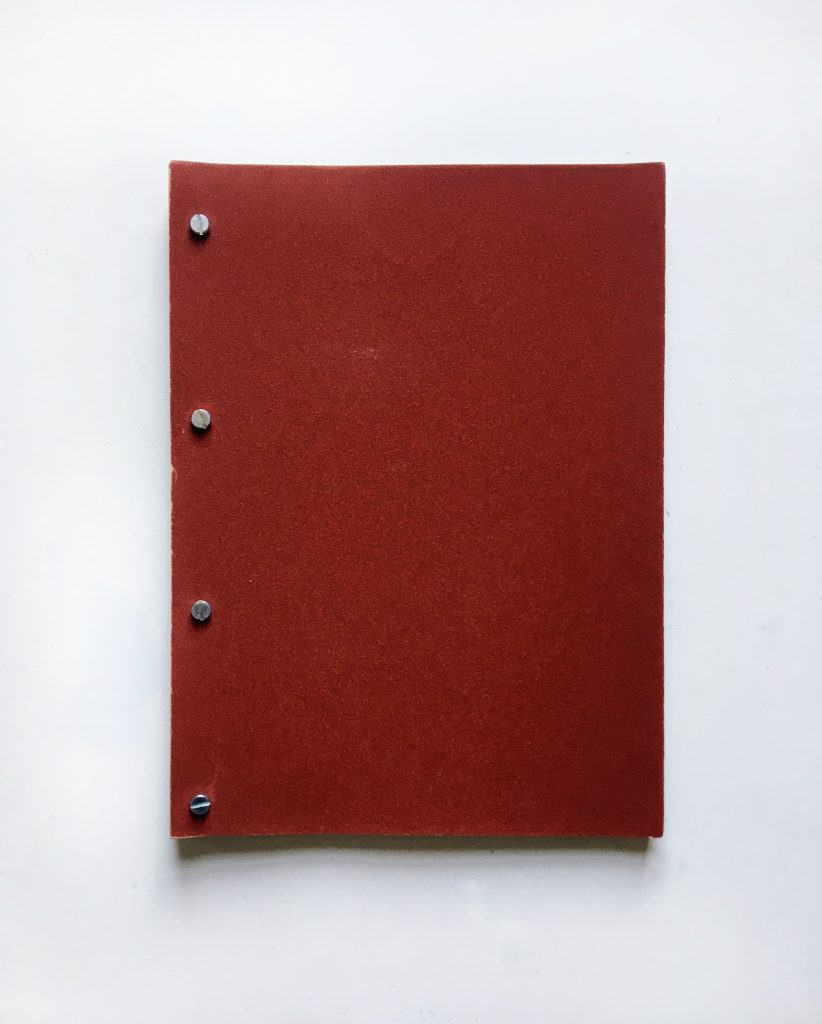

In Paris they take graffiti seriously. Just walking around the French capital leaves a certain kind of tourist full of admiration albeit for the hardcore damage rather than the usual attraction of towering ironwork. In particular the technique of ‘punitions’ whereby a train panel is covered with repetitions of a tag, rather than a larger piece, fires the imagination. Travelling around the city on the métro and the eye is drawn to another type of tagging in the form of the numerous abrasive marks scratched into the shiny metal doors of the carriage interiors. Hidden in plain sight most passengers must barely notice these colourless tags but a new publication MF.67D: Ligne 12 sets out to document some of those that can be found on the twelfth line of the subterranean transport system.