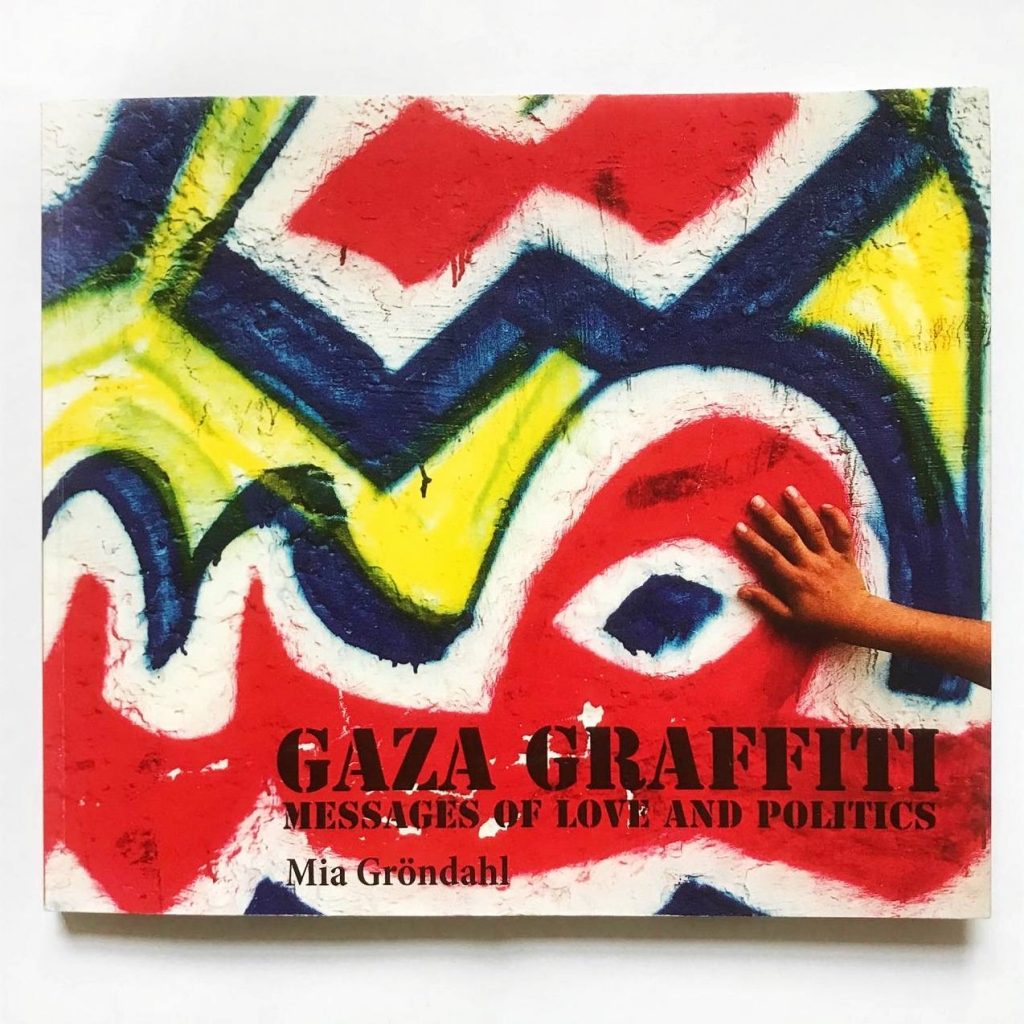

Seeing as today marks the start of Read Palestine Week I thought I’d see if I could find something about Palestinian graffiti to review. Almost everything I’ve seen about graffiti, or more precisely street art, from Palestine has been related to the West Bank Wall. In some ways the art that has been painted on the wall has drawn attention to it in a similar way to that which was put on the Berlin Wall. Various high profile street artists have travelled to the West Bank to make their statement on the wall, some largely with their western audience in mind, others more in earnest, before flying back home. So I was quite pleased when I came across Mia Gröndahl’s Gaza Graffiti: Messages of Love and Politics.

Published in 2009 the book documents graffiti made in Gaza by Palestinians over a period of seven years resulting in a collection reflecting the political changes in that time. Beginning with an essay describing how she first encountered the graffiti, Gröndahl explains that she was initially reluctant to focus on it in the face of the violence she was witnessing against the people around her. Although the book specifically dates the beginning of graffiti in Gaza to 1987, as a response to conditions during the first intifada, it was the new political climate following the Oslo Accords when Gröndahl noticed an explosion of it across the city.

Throughout the period Gröndahl discusses the walls of Gaza were themselves a battleground. During the Intifada it was not uncommon for the IDF to sweep into a refugee camp and demand that its walls be buffed of all graffiti. Later it was the Palestinian Authority themselves who declared war on graffiti, funded generously by the Japanese government, they dispatched patrols to buff walls in what ultimately turned out to be a fruitless exercise. This is a really interesting history to read about and Gröndahl does a good job explaining later graffiti beef between Hamas and Fatah and how their different ideological beliefs shaped the graffiti they produced.

…the walls of Gaza were themselves a battleground.

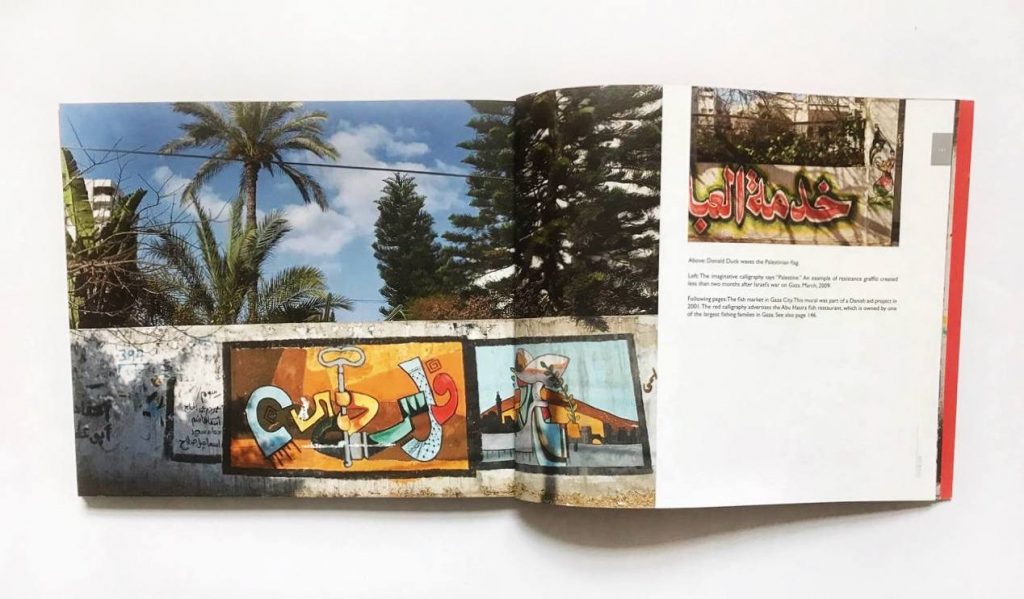

The author explains that she was hesitant to photograph the graffiti because she feared it detracted from the human situation. Despite this the majority of the images in the book foreground the city’s residents going about their lives or, as in many shots, groups of children posing for the camera. The colourful graffiti is always in the background but is an ever present component of the conflict; serving as propaganda, marking territory, memorialising the dead, and simply brightening otherwise drab walls. Some of the people captured in front of the graffiti are the artists themselves. Muhammad Safi proudly stands in front of a wall bearing the pro-Arafat slogan he has painted. He explains that his work came from a love of calligraphy, and how different political groups utilise and train their artists. To the uninitiated Gröndahl helpfully devotes a section to comparing the styles of the six scripts in Arabic and how they are used by graffiti artists in Gaza.

Not all the graffiti Gröndahl documented was conflict related however. Some of the walls have been painted to celebrate a wedding or commemorate the return of a resident from pilgrimage. The latter is something I have previously come across a brief mention of in a book by Sabrina DeTurk and have been intrigued about ever since. Several photos show this kind of graffiti which is used to welcome back someone from the pilgrimage to Mecca. Although they may not be directly connected, this kind of tradition has quite a long history in Palestine with scripts used to decorate banners that would mark the Nabi Musa pilgrimage.

Many of the images of people in the graffiti have been deliberately defaced for religious reasons but one recognisable figure that reappears untouched is that of a child with their back turned to the viewer. This is Handala, the character created by the Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali who was assassinated in London in the late 80’s. One of the most poignant pieces of graffiti is to be found on the final page of Gaza Graffiti showing Handala dismissing political affiliations and instead declaring “I’m Palestinian.”