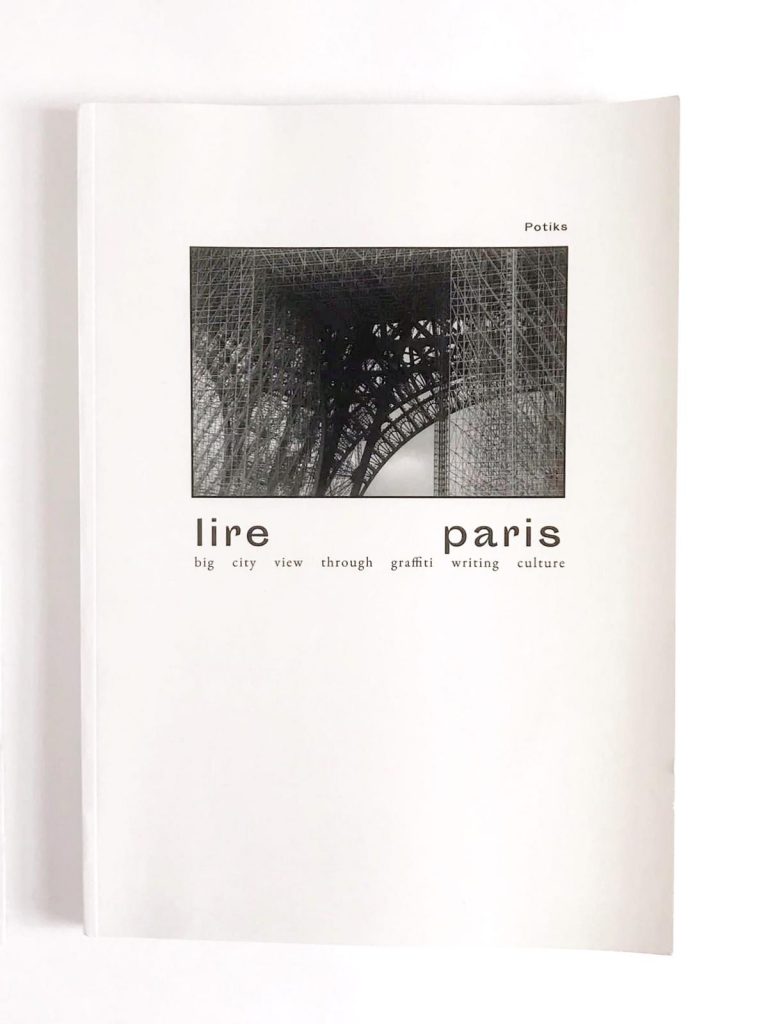

Introduced as an attempt at “catching the graffiti twinkle of Paris”, this is the latest publication from New Utopia Press. Documenting a short trip made by Potiks to the French capital Lire Paris is a tourist’s-eye-view of the city captured between stops at the many boulangeries and cafés to be found there. Potiks takes on the role of a self described flâneur; observing and soaking up the atmosphere of Paris. Or, more specifically its famous graffiti culture.

The magazine is made up of nicely produced photographs accompanied by short vignettes or observations about life, graffiti, and the experience of Paris. The majority of the photos are street damage; tags, shutters, rooftops with a few pages of track sides for good measure. There’s some lovely shots of graffiti adorning the higher reaches of tall French boulevards. A neoclassical statue of a reclining nude by the sculptor Léon-Ernest Drivier is adorned with a carefully placed tag. Potiks notes the irony of tagging being so ubiquitous in Paris that the palette of inked, scratched, and spraypainted pseudonyms simply fade into the background of everyday life.

One particular photo stands out; it shows a vast mural of a Parisian boulevard painted on the gable end of some typical Parisian apartment blocks. Various graffiti pieces have been rollered and chromed on along the bottom of the painting. Seemingly unintended, the result is a streak of brutal realism across this idealised vision of bourgeois Paris. This is the order and social contract that Potiks claims graffiti is intended to mock. Included toward the end of the magazine are the attempts to buff this very mockery off the city’s walls. Creating unintended patterns and stains these buffmarks fail at their task of ‘cleaning up’, instead conjuring a new aesthetic of accidental urban-art.

…this is a “rebellion against power and its violence”; themes which haunt the streets of the city…

At various times in its history the buildings of Paris have been subject to destruction and reconstruction. Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the centre of Paris was demolished and rebuilt according to the designs of Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Ostensibly to improve public health and relieve overcrowding, his vision was just as much about social control. Concerned about the rebellious populace in the area, the Parisian authorities wanted to be able to better control it through Haussmann’s designs. Indeed, as if to demonstrate just how severe and authoritarian this new Paris was, Hitler would later come to regard Haussmann “as the greatest city planner in history.” By the end of the twentieth century Paris was being redesigned again, this time to the demands of President François Mitterrand’s postmodern vision of it as a cultural capital of the arts. The fabric of Paris has been repeatedly demolished and rebuilt over again to suit the prevailing ideology of the times.

It was Walter Benjamin who would traverse through the remnants of the pre-Haussmannian Parisian arcades, collecting scraps of consumer culture, in order to reassemble an understanding of how capitalism was experienced. His work has been hugely influential and remains relevant today, seeming to prefigure the modern digital age. Indeed, the ways in which graffiti is viewed and collected online often seems to echo Benjamin. Of course, Lire Paris is not online but its exploration of Paris is embedded in the digital zeitgeist. One section shows shots snatched from a tunnel as the Métro darts through it. The images only revealing themselves once loaded onto a computer to be reproduced in print.

“History layers” writes Potiks beside a photograph of a wall with the ghost of an ACAB graffed on it. The wall’s render has been partly removed revealing the brick beneath. Apparently this is a “rebellion against power and its violence”; themes which haunt the streets of the city and inform the graffiti Lire Paris documents.