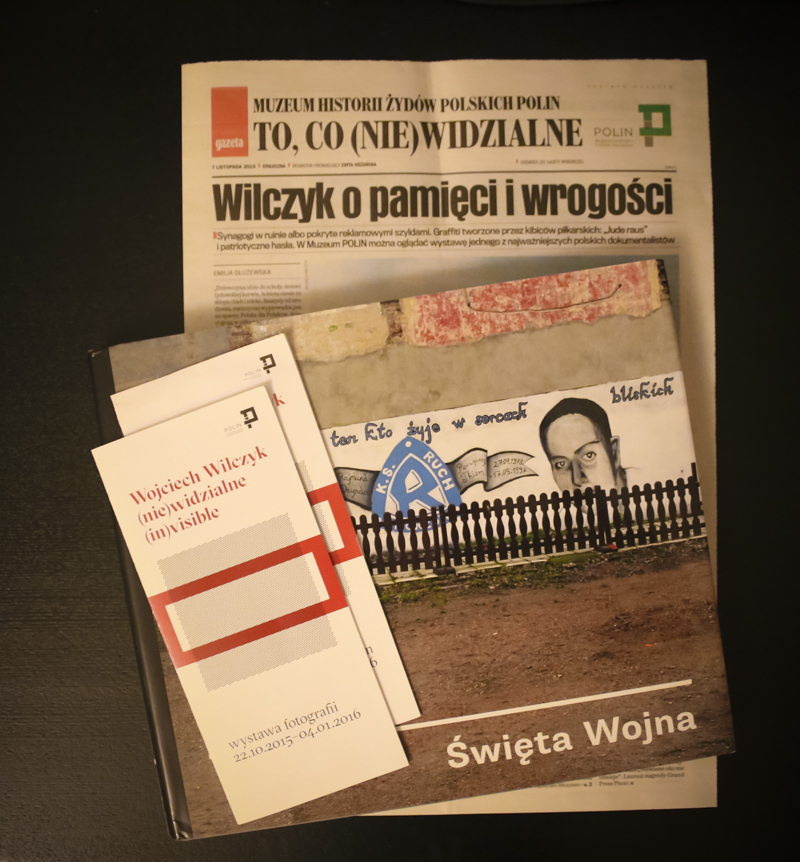

I recently went on a trip to Warsaw and whilst there I visited the Polin museum to see an exhibition of work by the photographer Wojciech Wilczyk. The exhibition showcases some of the photos from his ‘Holy War’ project which were made into a book titled Święta Wojna. The book is a collection of nearly four-hundred photos of football graffiti from Poland. As a fan of both graffiti and football I was bound to be interested in this book really.

The supporters in Polish cities have proper turf wars with graffiti used to mark out a clubs area, they even have graffiti reports in hooligan magazines. A quick search on Youtube yields loads of videos of this stuff such as Cracovia lads taking out a Wisła Kraków mural or a GKS Katowice piece which was subsequently altered by some Ruch Chorzów fans. Święta Wojna starts with an introduction and glossary of terms in Polish but fortunately I picked up a translation of it at the exhibition. English football clubs have unique and often convoluted identities and their Polish counter-parts are no different so this was quite helpful.

“One cannot be Polish, or think about being Polish, without also thinking about the Jews…”

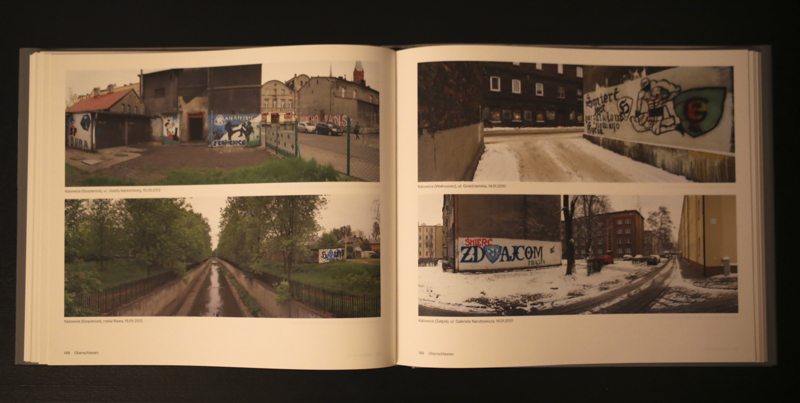

The first chapter is called ‘Town of Knives’ and is set in Cracow. In Poland there is an agreement amongst hooligans called the Poznan Pact that bans the use of weapons in fights. The chapter title is in reference to the fact that the two main Cracow teams, Cracovia and Wisła, refuse to adhere to this pact. The two teams have an intense rivalry known as the ‘Holy War’ (also the title of the book) which is reflected in the graffiti. The chapter mainly shows tagging, tags over tags, club crests and basic murals. I suppose the dominance of tags and fairly simple letters is a result of both the intense rivalry in the city where graffiti will quickly get taken out, and by the authorities buffing the sides of housing blocks. ‘Oberschlesien’ is the title of the second chapter which focuses on several rivalries in the Upper Silesian area of Poland. Here the streets look a bit more rundown. Some walls are covered top-to-bottom in tags and obviously haven’t been buffed in years. There are also a lot more murals and complicated productions which display the colours of Ruch, GKS, Górnik Zabrze and Polonia Bytom. The final chapter is called ‘Żydzew’ and shows the rivalry between the fans of ŁKS and Widzew across the streets of the city of Łódź. Here the walls are similar to Cracow with a lot of tags and simple pieces that have been gone over and crossed out but there are also some more complicated productions.

The graffiti doesn’t just concern football but also displays the antisemitic and far-right leanings of many of the groups of supporters. The troubling topic of antisemitism on prominent display in some of Poland’s cities is what the book and the Polin exhibition confront. In many of the photo’s the walls are adorned with swastikas, antisemitic slogans and references to the Holocaust. Here the term ‘Żyd’ (Jew) is used as an insult. The title of the third chapter is the taunt aimed at Widzew fans when their clubs name is corrupted to ‘Żydzew’. In fact both sets of fans of the two Łódź teams write ‘Żyd’ to insult each other. Looking through the book I remembered reading the historian Padraic Kenney who observes that the “Polish identity is forged in the constant presence of antisemitism. One cannot be Polish, or think about being Polish, without also thinking about the Jews, about their presence and absence, and about the demarcation between the two nations”. Some of the graffiti in Święta Wojna certainly demonstrates this preoccupation.

This leads me on to a quick point about how observers interpret the graffiti they see. Anyone looking at the book may understandably be shocked by some of the graffiti yet, in the exhibition, there is a video of passersby going past a piece of graffiti declaring ‘kill the Jews with machetes’ without a second glance. Although this could be taken as an indictment of Poles tolerance of antisemitism, their casual attitude probably reflects the context. The particular graffiti is in Cracow where one of the teams are referred to as the ‘Jews’ by both their own and opposing fans and where machetes have notoriously been used as a weapon by some of those fans. Presumably this particular graffiti was viewed in that context rather than taken at face value, although that doesn’t dismiss the photographers offence at the scene.

Apart from its antisemitic content I think the graffiti also signposts the particular identities of football fans and the histories of clubs in Poland. For example fans of the team Ruch use the German spelling to refer to their region (hence the title of the second chapter). Some Silesians have a complicated identity torn between Germany and Poland and the graffiti photographed there often looks like some sort of extreme display of this. The swastikas are mainly painted by Ruch fans which sets them apart from other right-wing fans who use the celtic cross instead (on page 223 the anti-nazi slogan ‘Hycler’ appears painted on a Łódź wall). The swastika appears to be used as a crass statement of an obscured German identity as much as it is a political expression. Another Ruch piece, on page 143, that declares “Meine Vaterland its Oberschlesien” reflects this too. Other graffiti in the book point to peculiar club identities as well. The association of Cracovia as a Jewish team goes back to before the Second World War when they had connections to the socialist leaning Jewish club Jutrzenka. Jutrzenka’s rivals were the Zionist team Makkabi Kraków, who favoured Wisła, and when the two teams played it was known as the ‘Holy War’. So the graffiti found in present day Cracow doesn’t just reflect modern antisemitism but can also be seen as a sign of a longer relationship between the city’s clubs and the Jewish population that once lived there.

Wilczyk has taken some brilliant photos and I found the book to be a fascinating and thought provoking look at the football graffiti subculture in some of Poland’s cities. The exhibition is definitely worth a visit too especially as the streets around the Polin museum are host to their own graffiti battle between Warsaw‘s two main teams.

Pingback: The Philosophy of Muralism – Graffiti Review

Pingback: Hooligan Surrealism – Graffiti Review

Pingback: Nationalist muralism in contemporary Poland – the GRAFFITI REVIEW

I’m from London but now live in Poland, and I’ve always loved the graffiti and graff culture back home in the UK. I dislike football though, for a number of reasons and I absolutely fucking despise Polish football graffiti. Its ugliness is only surpassed by its ubiquity: scrawled shite put up there by mouthbreathing macho pricks. Hideous shite everywhere you look, all over every city with more than about 10 people in it.

As well as having the most football graffiti, Poland also has the most dicks spraypainted on walls of any country I’ve ever been to. I think that actually correlates. Polish football graffiti and scribbled dicks are what you get when a monocultural, overwhelmingly white, conservative, hardline Catholic, patriarchal, machismo-sodden, women’s-rights-denying, gay-hating, xenophobic, backward society like Poland’s picks up the spraycan. I.e. nothing good whatsoever. Fuck Polish football graffiti, with the utmost sincerity.