I can’t say I know too much about Swiss graff as I’ve only briefly set foot in the country with just enough time to slam down a cup of coffee and leave. So I approached Zee City, the new book about graffiti and hip-hop culture in Zurich, with an open mind. As I read through the book I learned a lot about the early influences on Zurich, how they shaped the scene there, and in turn how the city has affected graffiti elsewhere. The story begins typically enough when rap videos or films like Wild Style and Style Wars were shown on European tv. However from there Zurich has its own particular story to tell.

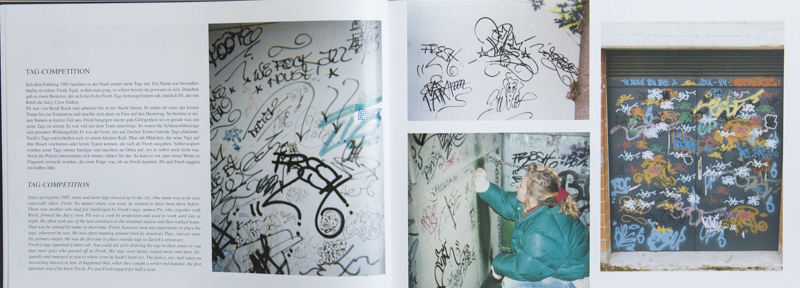

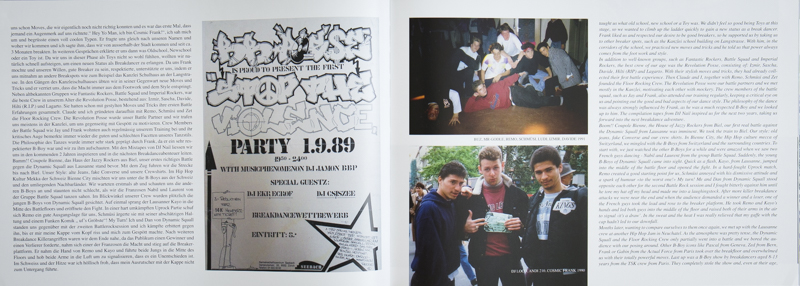

Zee City can be roughly divided into two parts; walls and trains. The first half of the book looks at the beginnings of graffiti in Zurich with different people describing how they got started, early crews, and lots of photos of old school walls. It’s clear from the start that graffiti in Zurich was inseparable from the burgeoning hip hop scene. Ducal Daddy Fresh provides an in-depth history describing how he caught the hip hop bug and painted his first graffiti in 1983. The way he tells the story helps bring to life the energetic and eager young graff scene that quickly emerged. In the next few years trips over the borders brought back new influences from Paris and German cities such as Munich. Aside from new styles being imported there were also two particularly influential foreign writers in the Zurich story. The first of these is Rammellzee, who in 1985 exhibited some of his work alongside some live performance. In the same year local writers were also visited by Phase 2. As well as providing first-hand knowledge of graffiti’s roots, Phase 2 seems to have energised the Zurich writers he met and inspired a new focus on letter styles.

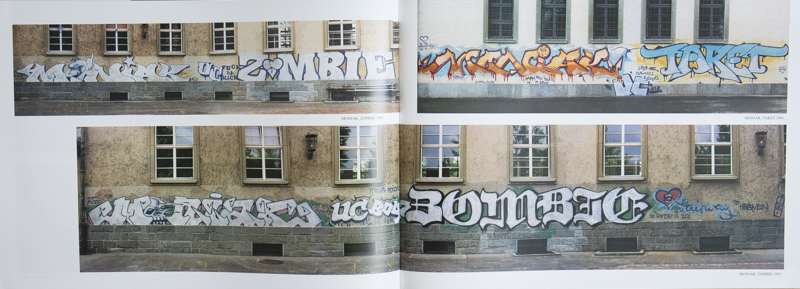

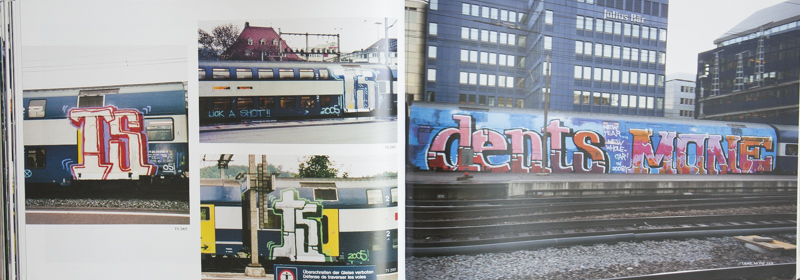

The book smoothly carries on from this early history with various writers, DJ’s, and b-boys telling their stories. In between are cool shots of early pieces, street bombing, productions, and breakdancing. The text by Lord describes how the streets along a central tramline became the battleground for graffiti artists to display their work. Eventually this route hotted up and so the graffiti spread out along other tram routes into the rest of the city. As the story ebbs and flows through various zero tolerance initiatives it’s around a third of the way in, as the 90’s begin, that the canvass changes from the wall to the train. This is where the narrative goes from slightly more reflective writing to descriptions of experiences and motivations. It’s also where the VTO crew enter the story. Described as Switzerland’s very own graffiti supergroup they set the bar for the train-writing scene, producing underground gesamtkunstwerk, and doing the country’s first double-decker wholetrain. Another group featured over a load of trains is the TS who used a style of unobtrusive top-to-bottoms to successfully get their message out. This part of Zee City is illustrated with a load of pictures of various trains and styles, including work by tourists, and a few shots of Swiss writers abroad – even as far as Japan.

Throughout the book Zurich’s writers put forward their own analyses of graffiti. In a piece by Prodomo he argues that it is a liberating act and highlights its Anarchic nature. Not only is graffiti empowering on an individual level but its expression is also a ‘social contribution’ that questions established truths. This leads me on to Gen whose chapter is particularly uninhibited. His essay is partly an ode to his mentor Rammellzee, part philosophical theses, and at times a political rebuke. The opening scene is set one evening in the New York subway. Gen and Rammellzee are tagging the inside of a train. This is what Gen describes as the quest for identity by creating ‘frozen sounds’ using their own letters. They’ve inherited this human quest that stretches all the way back to prehistoric cave paintings. For Gen the graffiti subculture is more than an instinct though, it is also a direct challenge to power and the status quo. Obviously this leads on to philosophical questions too; is graffiti just another avant-garde art form expressing “the basic biological programs of mankind?”; is art anything more than a way to avoid human facts of life and death? At points this all gets slightly baffling and occasionally the writing seems bitter but it is also a really engaging read. Later in the book Arez emphasises Gens presence in Zurich’s graffiti when he says that it was he who came closest to developing a ‘Zurich-style’. As it was, rather than their own style, the city’s writers developed their own method of ‘blanket vandalism’.

Arez is yet another contributor to Zee City who writes intelligently and isn’t afraid to speak his mind. He critically reflects on graffiti in Zurich as a sometimes unimaginative yet active scene. Arez also pays tribute to the Fourteen Kay magazine which became an early institution of European graffiti. Started in 1988 the publication was one of the first hip hop magazines in the world and at its peak had a print run of 7000! The importance of Fourteen Kay is emphasised with mentions throughout the book and there’s also some interesting texts by those involved with its production. One of these is a photographer called Beka who religiously documented Zurich’s graffiti. In fact he was such a regular to the city’s train yards that he was allowed the use of an employees bike on his visits!

Although the editors say that the book can’t tell the complete story of graffiti in Zurich, Zee City does seem to be pretty exhaustive. There is a lot of content here, from hundreds of pictures to dozens of articles that describe the wider hip hop scene, individuals experiences, and the beginnings of the movement. In the early parts of the book there are allusions to the activism of the time such as the anti-apartheid movement. Elsewhere a flyer for a ‘Stop the Violence’ party is reproduced and there’s a great piece written by the feminist Revolutionary Women’s Art crew. It could have been interesting if these interactions with contemporary politics had been explored a bit further. Aside from politics there’s a strong intellectual vein running through the book. According to DJ Nail, Zurichs hip hop scene brought people together to “philosophize about God and the world”. Evidence of this can be found here with the many engaging and intelligently written articles. On the whole there’s not much that can be criticised. Zee City is well produced, there’s lots of good anecdotes, the combination of graffiti and the wider hip hop movement is done well, and most importantly it has some wicked graff.