Before I begin this review I have to admit to being the type of ‘non-specialised sceptic’ who Andrea Baldini criticises in the recent Un(Authorized)//Commissioned book. The publication he writes in can be regarded as a curators guide to exhibiting graffiti. This is not a topic that would usually appeal to me so, not being a particular expert nor a lover of art-galleries, I approached the book with mild cynicism. However the book brings up some interesting ideas that are worth discussing and has changed my opinion to some extent.

Un(Authorized)//Commissioned actually came about following the 1984: Evolution and Regeneration of Writing exhibition held in Modena in 2016. The exhibition, curated by Pietro Rivasi, aimed to set a new precedent in the way graffiti is displayed within institutional spaces. Rivasi broke with established fine-art modes of display and instead focused on how to represent the graffiti on its own terms. This meant doing away with canvasses or pieces ‘reclaimed’ off the street and using photography and video instead. In the first part of Un(Authorized)//Commissioned Rivasi uses his exhibition as a guide to how graffiti can be exhibited appropriately. Through the second essay in the book Baldini provides the theoretical underpinning to this approach.

Rivasi’s method for exhibiting graffiti came about after years of involvement with graffiti. Having begun painting trains in the mid-nineties he was soon engaging with ‘official’ digital media sources and little over a decade later founded his own gallery. Since then he has been involved in various events and projects such as The Bridges of Graffiti in Venice or the Vicolo Folletto gallery in Reggio Emilia. However Rivasi tells me he has became frustrated with the art-establishment who, “usually knowing almost nothing about the uncommissioned urban art world, can decide who the artists are among all these vandals (or just give some outsider the ‘street tag’ label even if they never did much in the streets), and put them in important institutional places and auctions.” In reaction to this, in Un(Authorized)//Commissioned, he proposes ‘getting up’ as the criteria for displaying graff in institutional settings while also emphasising the use of photography. Rivasi also embraces ‘extra-gallery’ activities as a way of highlighting “the schizophrenia of a society that on one side persecutes and condemns those who paint on surfaces with no authorization while on the other recognizes its value by giving it space within the most respected modern art institutions.”

It may well be that in the modern digital age more graffiti is viewed as photos or videos than on actual walls. However to state that a train or a wall is not even relevant is bewildering.

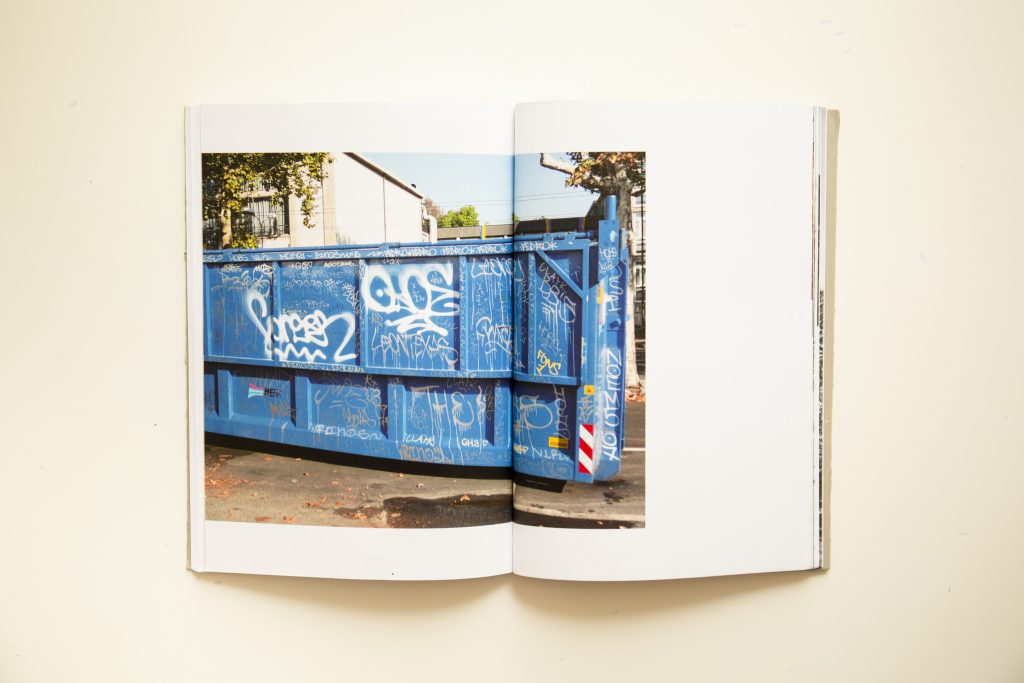

The first idea of incorporating ‘getting up’ as a method to curate graffiti in a gallery is quite simply to show graffiti on its own terms. This way, rather than the usual “sugar-coated spray artists without street credit”, those who have put in the real work will get shown. Rivasi also observes that giving space to relevant activists resulted in illegal works appearing concurrently to the exhibition. In effect extending the gallery show into its natural environment. ‘Getting up’ is also, importantly, paired with photography as it gives more context to the work than, for example, a reproduction on a canvas. Rivasi also highlights the immediacy of the photography. He tells me that, while photographers such as Martha Cooper or Henry Chalfant “documented a phenomenon, what I’ve tried to do is to show photos or videos that are meant to be artworks. Also I wanted to have very fresh, contemporary, acts of vandalism in the show because photos from the 70’s, in my view, lose all their power to ‘shock’ the audience. They are no longer perceived as something negative for taxpayers… Of course back in the early 80’s a Dondi photo could have had the same effect.”

Up to this point the book is quite straightforward however the second chapter by Baldini, which provides the theory to Rivasi’s work, becomes more complex. He argues that if graffiti is to retain its authenticity and subversiveness when entering the space of a gallery then it must be displayed in the appropriate way. He believes that through Rivasi’s approach this can be achieved. The photograph is the best way to do this because it is an established method of recording graffiti but, more than that, it is actually an integral part of the whole process of the production of graffiti. By using photography to display the activists who are ‘getting-up’ their graffiti is given context and avoids being institutionalised. Rivasi’s technique challenges the “assumption that criteria for evaluation of graffiti must comply with those generally used for other art forms.”

Where Baldini becomes contentious is his assertion of the photograph as the original artwork and, in fact, primary mode of viewing graffiti. While he accepts that “we sometimes appreciate tags, throw-ups, and pieces ‘live’” actually “the medium that is relevant to appreciation does not include things like the wall, train, paint, and techniques to produce an example of graffiti, but photographs, videos, and other varieties of technology…” It may well be that in the modern digital age more graffiti is viewed as photos or videos than on actual walls. However to state that a train or a wall is not even relevant is bewildering.

Baldini’s argument, that the photograph itself can be considered the original piece of art which is a snapshot of the ‘performative’ aspect of graffiti, is something the influential critic John Berger also considered. In Understanding A Photograph Berger describes a photograph as a record of the event it captures. He writes that “all its references are external to itself’; put simply what is important about a photograph is the viewer’s understanding of its context. So when Baldini describes a photograph as a “representation of the writer’s performance” he stresses that the graffiti, like the photograph of it, is merely one part of the whole graffiti action.

…a gallery is a ritualistic space in which specific behaviours and states of mind are created that are at odds with the practice of graffiti.

Any piece of graffiti usually has an extremely limited lifespan before it inevitably gets buffed so photography has always been an important part of graffiti culture. Baldini uses the rhetorical example of a long gone Dondi piece which, through existing photographs, can still be appreciated. He makes the convincing point that graffiti is largely viewed through a secondary medium such as a photograph. Rivasi tells me how he “tried to explore this field a bit further, bringing very active contemporary writers into the museum with illegal paintings photos or videos as proper artworks. Since they are ephemeral and the original gets destroyed, so the photo becomes ‘the original’ or at least the only existing proof that something ever happened” Baldini understands that the context of a photograph of graffiti, what he calls its ‘performance’, is important. However he seems to disregard the context in which the graffiti exists outside of the photograph. As Berger says “it is more useful to categorize art by what has become its social function.”

What I mean by this is that while a photograph displayed in a gallery can reveal contextual information it has limitations. When the photographer captures the image they do so in a particular time and place. Whoever then views the photograph can only understand the image using whatever experience or background knowledge they have. However the setting of a gallery has its own specific context in which art will be viewed. Here I think the essay ‘From the Street to the Gallery’, by Alexandra Duncan, is useful. Her article is from an academic book called Understanding Graffiti. Duncan’s contribution is about the inseparability of graffiti from its context, and more specifically how this context changes in a gallery space. The gist of her argument is that a gallery is a ritualistic space in which specific behaviours and states of mind are created that are at odds with the practice of graffiti.

Duncan writes that “graffiti function as a democratizing form of communication in the open air of modern cities and towns. It is also essential to recognize the differences in audience interaction with imagery on the street and in a gallery, which is characterized by hierarchical systems of judgement and valorization.” I think this is where Baldini’s argument falls short. While he argues that by displaying original photographs the ‘rebelliousness’ of graffiti is retained he forgets that, in practice, the graffiti is being viewed in a completely different context.

Ultimately Rivasi aims to have illegal graffiti displayed authentically, on its own terms, as proper art. Recognising the importance of photography for recording and viewing graffiti means that his methods, in theory, are not too dissimilar to the millions of digitised images that are curated on the internet. Coming from an initially pessimistic view of the book’s subject I think Un(Authorized)//Commissioned sets out some complicated but well thought out ideas. The commercialisation of street-art and the opening of new museums, like Urban Nation, means it can only be positive for Rivasi and Baldini to try and set out an alternative to how graffiti will, in turn, be displayed in such institutions.

*Photographs of the 1984: Evolution and Regeneration of Writing exhibition were taken by Paolo Terzi.

Pingback: Between Gaúcho’s and Cats – the GRAFFITI REVIEW

Pingback: How B****y didn’t conquer the Middle East – the GRAFFITI REVIEW