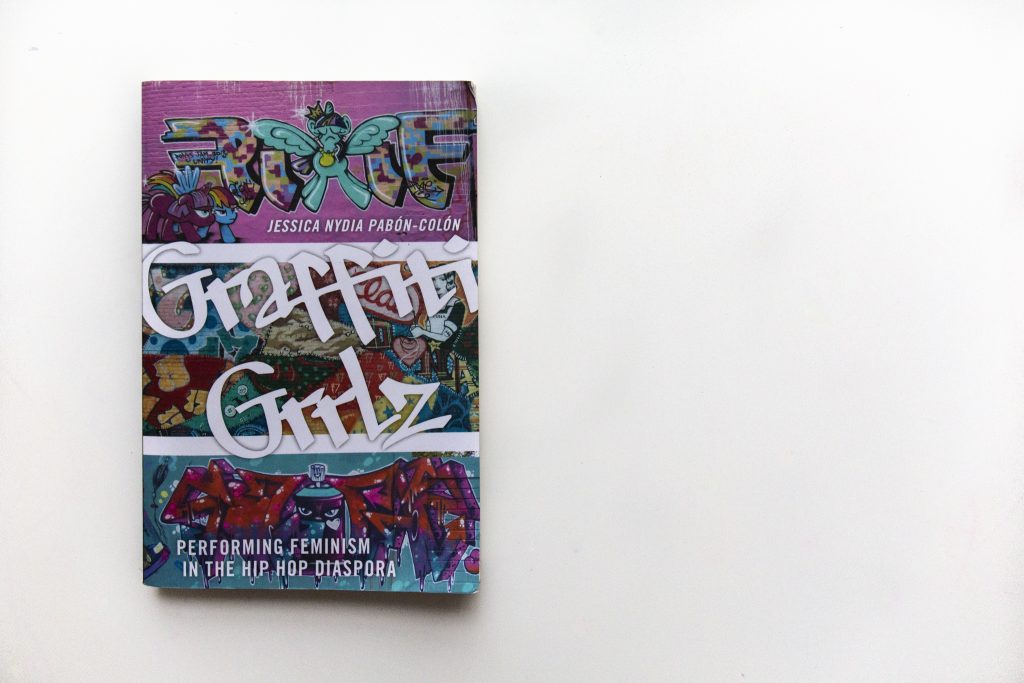

When I first picked up Graffiti Grrlz I thought the book might contain an argument along the lines of how women are excluded from the masculine graffiti subculture. Actually the book’s author, Jessica Pabón-Colón, has written a positive account of female involvement in graffiti. That’s not to say the book paints a completely rosy picture but that it concentrates on how women practice and contribute to graffiti in an empowering way. Pabón-Colón wants her book to weave the “individual stories (of female participation) into a narrative about how they navigate their experiences as a collective within the subculture”. Through this narrative Graffiti Grrlz provides new and original insights into graffiti. The book explores the activities of female writers, based on interviews with the author, and how they ‘perform’ feminism through the graffiti subculture. From Africa to South America, graffiti jams to graffiti collectives, digital social networks and the internet archive there’s a broad range of experiences covered.

With any text it’s useful to think about the language used and why. Here the initial questions pop out from the front cover; why grrlz, why feminism, and why hip-hop? How are these words linked and what is the purpose of the language used. Pabón-Colón deals with this early on in her intro by rigorously explaining her intentions and why she has chosen specific phraseology. So throughout the book Pabón-Colón uses the word ‘grrlz’ as, she explains, it fits both with this unconventional youthful subculture while drawing on an existing feminist tendency to switch up spellings. She thinks using ‘grrlz’ can also help to relate the Hip Hop element of her study to “Riot Grrrl punk-music subculture.”

The two important words that really shape this book though are ‘feminism’ and ‘Hip Hop’. To be honest I was a bit surprised to find the latter in the book’s title. Pabón-Colón argues that, while graffiti may have been artificially packaged as part of Hip Hop, it was as part of this ‘brand’ that graffiti spread around the world. Really she uses Hip Hop studies as a tool for her own research. While she links the two she also discusses why writers may often reject the Hip Hop label. For instance she points out that Hip Hop is perceived as a black, male, and heterosexual subculture the ‘performance’ of which ends “at a racialized line of authenticity drawn to maintain ownership”. However this vision of Hip Hop is at odds with many of her protagonists whose experiences of graffiti do cross this line. When distancing graffiti from Hip Hop its practitioners aren’t being accused of whitewashing it though. Pabón-Colón isn’t trying to suggest that graffiti is some kind of cultural appropriation but that it is “rooted in a specific ethnocultural tradition and performed felicitously by individuals not of that ethnicity”. Wow…! Bearing in mind that this is still just the introduction; there are a lot of ideas to digest in this book.

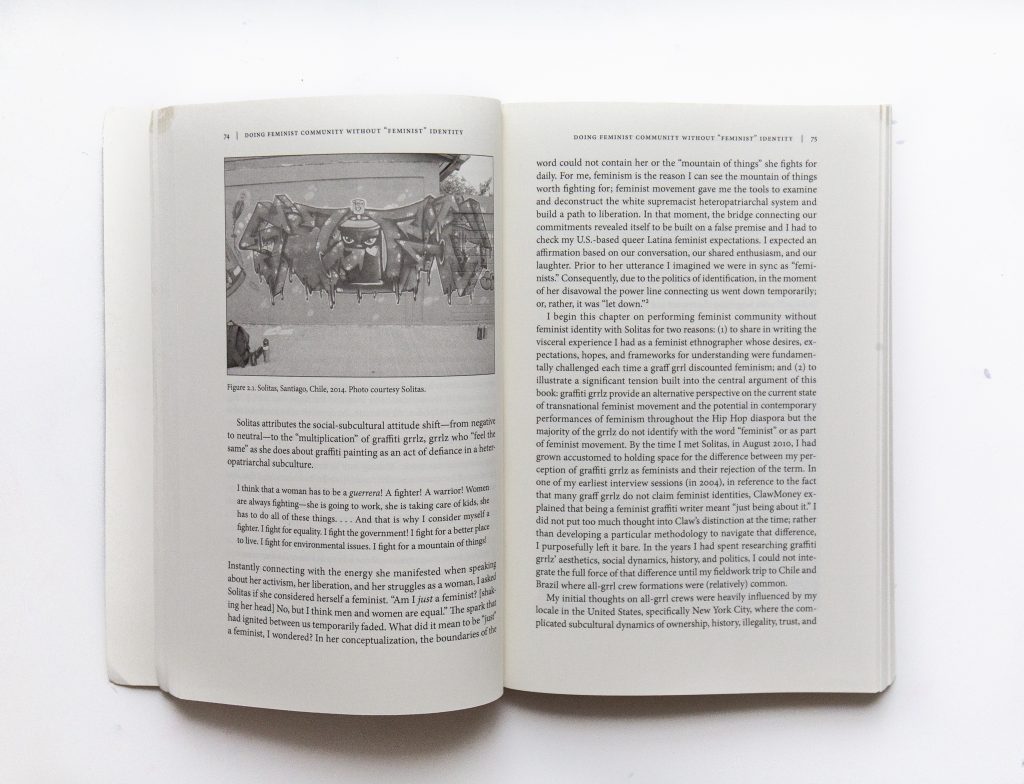

Curiously enough Pabón-Colón’s arguments seem repeatedly at odds with the opinions of the grrlz themselves. Throughout the book they challenge graffiti being Hip Hop and fail to call themselves feminists.

As I was working my way through the book I kept returning to this framing of graffiti around Hip Hop. In Graffiti Grrlz viewing graffiti through the lens of Hip Hop is a useful way of understanding how graffiti and race are related in America. It seems less useful when considering graffiti beyond the borders of the US. I could bring in two other publications here; Jacob Kimvall’s The G-Word and Kilroy’s Conformity by Antny Kreeg 47. What’s interesting about these two books is that both authors choose to reference Jazz in relation to graffiti. Kreeg 47 discusses the ‘Kilroy was here’ graffiti as an emblem of conformity to American imperialism. Against this the author positions movements like Bebop, that emerged in the ‘50s, and later graffiti as nonconformist. If graffiti emerged as a deviant expression in the US it hasn’t always retained this spirit as, in Pabón-Colón’s words, it “traversed the globe under the moniker of ‘Hip Hop culture.’” In his book Kimvall compares how the graffiti on the Berlin Wall was used as propaganda during the Cold War to the similar use of Jazz. Musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong were sent on tours to Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the USSR as ‘Jazz Ambassadors’ of the United States. I’m not sure how far the case could be put that Hip Hop has served as a tool of soft diplomacy but graffiti has certainly been useful as an expression of American culture up to the present day (an example of this are the specific occasions graffiti has been used by the Chinese state as a propaganda tool). The moral panic that ushered in graffiti as the dominant urban art-form was arguably about a fear of black youth taking back control of their urban space. But when one of the female graffers in Graffiti Grrlz distinguishes graffiti from Hip Hop by asking “…where are the Black graffiti writers?” this question doesn’t really translate across the Atlantic. Later in the book a white South African writer, who is concerned about her painting being perceived as “another kind of colonization”, turns this dynamic on its head given a different yet highly racialized space.

This brief outline of the Hip Hop question leads on to the feminist one. Pabón-Colón argues that a narrative of female exclusion from graffiti is down to an academic prejudice that has only ever considered male participation in subcultural activities to be significant. Female participation often hasn’t been seen simply because it hasn’t been looked for nor expected. She goes on to challenge the assumed universality of graffiti expressed in various literature on the topic. This universalism hinges on the presumption that gender (or race, or class) does not matter to the reading of graffiti and so, by extension, gender doesn’t matter to the writing of it. Pabón-Colón disagrees with this notion arguing that grrlz will inevitably have different experiences of the graffiti subculture because of their gender. Her main idea is what she terms ‘feminist masculinity’. Not only can graffiti be an escape from “the pressure of normative, white Western femininity, and the social and political limitations grrlz experience because of their gender.” This is her contention that female participation in graffiti challenges gender stereotypes and allows grrlz to own ‘masculine’ characteristics, such as assertiveness or confidence. This is a deviation from femininity but also a deviation of masculinity.

Curiously enough Pabón-Colón’s arguments seem repeatedly at odds with the opinions of the grrlz themselves. Throughout the book they challenge graffiti being Hip Hop and fail to call themselves feminists. However this disjunct leads Pabón-Colón to much more nuanced understandings. So, for instance, towards the end of the book she discusses why the South American ‘graffiteras’ reject the feminist label. This could have haughtily been put down to their own ignorance but instead Pabón-Colón concludes that this is a failure of Western feminists to “make room for truly alternative performances of feminism, despite years of scholarship and activism demanding that very thing.” Again the Hip Hop label could run the risk of pinning graffiti down as merely an extension of another subculture and ignoring its diversity. Pabón-Colón avoids this trap and uses it as a useful way of explaining the racialised and gendered dynamics of graffiti. Elsewhere, despite deciding not to focus on individuals writers who identify as such, she asserts that “graffiti writing is queer.” Rather than “any specific reference to queer sexual acts” her claim is “an attempt to mobilize the challenges to normativity enacted by writers”. Pabón-Colón says that describing graffiti as queer “feels provocative” but unfortunately doesn’t describe the idea much further. If I had to give a criticism of this book then, as with most academic books I’ve reviewed, it would probably be about the vocabulary. In Graffiti Grrlz this is specific to the authors feminist scholarship. So when Pabón-Colón brings in the idea of transephemera I did start to feel a bit lost. Sentences describing “the coproductive and codependent hegemonic tyranny of heterosexism and sexism…” can be a bit hard to get through. Although, to be fair, she goes on to clarify that by heterosexism she means “the institutionally supported ideology that heterosexuality is the norm to be valued above all else” while sexism is defined as “the institutionally supported ideology that cisgender males are the norm to be valued above all else”. However, putting this grumble aside, Pabón-Colón is generally spot-on and delivers some brilliant observations. Her statement that graffiti is a “relentless public commentary on the politics of ownership and the question of public space under settler colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism.” is typical of these!