By Andrew Finch

There was once a sprawling network of river people who inhabited the banks of Britain’s waterways. They had their own economy, customs, mythologies, and methods of reading the water’s flow to indicate incoming storms and floods, a vital role in informing land dwellers of when the foreboding channel was prone to causing destruction. They had a desire to live away from the order of natural belonging on the inner land, seeking refuge where the river flowed like jewels through the city…

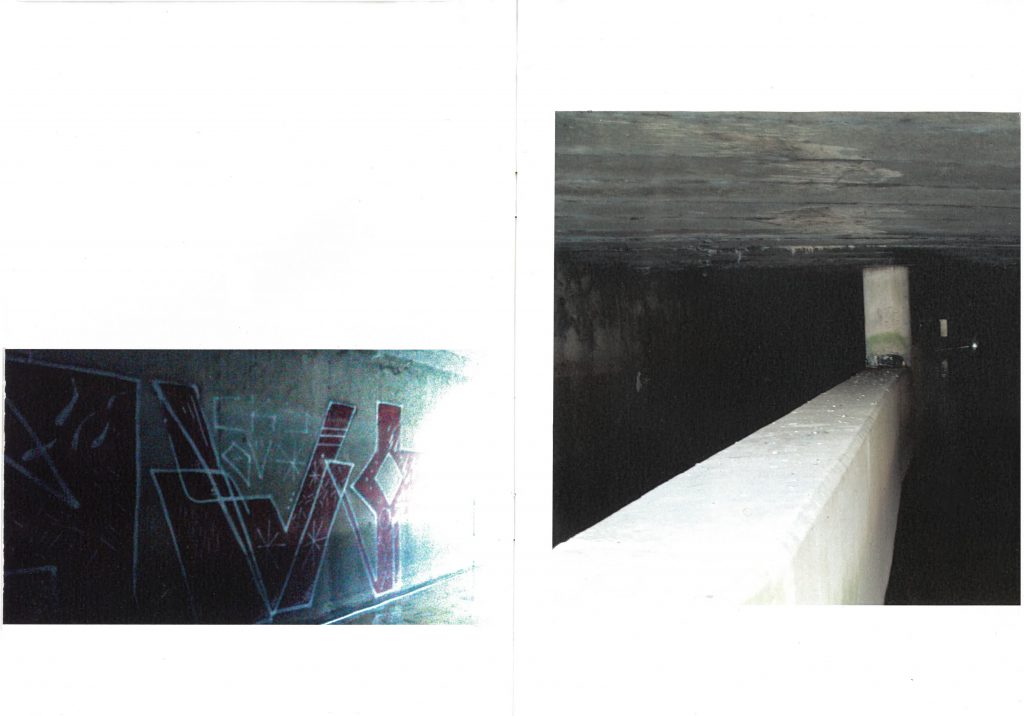

Track & Field’s latest publication, British Waterways (part 1), is part ethnographic river study and part documentation of an ongoing graffiti mission. PE! and Mutant are our faceless guardians of the waterways, suited in oversized North Face jackets and shod in scuffed wellington boots. Within the claustrophobic confines of embankment walls and tunnels where daylight scarcely penetrates, they could lurk in any of Britain’s interconnecting rivers. In one of the photos, there lies a clue: an uprooted street sign cast into the water, clinging to a concrete divider, reads Wollaton Road, which points us to Nottingham, a stone’s throw from the River Leen.

The River Trent is the third-longest river in the United Kingdom. From its source in Staffordshire, it courses through Stoke-on-Trent, Stone, Rugeley, Burton upon Trent, and Nottingham, eventually emptying into the North Sea between Hull and Immingham, in Lincolnshire. With all major rivers, it has multiple tributaries, including the River Leen, which runs quietly out of sight to onlookers. Due to flooding risks and complaints from residents, council efforts have attempted to push its channel into hidden concrete culverts, an all-too-familiar story for urban rivers and those committed to archiving their memories before regeneration.

Those looking to gain insight into the current state of Nottingham’s graffiti scene may be disappointed. Few photographs are devoted to the colourful throw-ups, in which green and purple acid drip around Mutant’s b-movie-style protruding eyeballs and codified symbols and numerology in PE’s abstractions. The fading markings of older pieces left by those who have prowled through these parts are perhaps more intriguing, although these ghost traces are sparse. This appears to be within a relatively untouched environment for intrepid writers, and it is the environment that takes centre stage in this publication.

Today, the river people of Britain’s waterways have become sparse.

PE! and Mutant offer us a subterranean glimpse into this rarely-seen world. Stalactites cling to tunnel ceilings, head torches shine on fissures unseen for decades, and mossed watermarks indicate the flood levels of subsequent seasons. Fading logos on discarded litter become cultural artefacts. The recesses of the brutal architecture constructed around the water are lessons in aggressive urban planning. Inside a shopping trolley hurled into the water is a heron’s nest where its eggs wait to hatch. Take this away, they seem to say, and you risk damaging an adaptive ecosystem that manages to thrive without further disruptive council intervention.

Urban rivers take on an alternative atmosphere at night, both eerie and otherworldly, their black surfaces are unknowable thresholds. They are also tranquil and calming environments; the acoustics within tunnels belies the constant humdrum of the city above. In their nocturnal photographs, PE! and Mutant’s head torches create dazzling azure refractions off the water surface where their camera shutter speeds have proved too slow for the dancing light. We see the poetic movement of two friends trudging into the unknown, exploring the secret arteries of the city together, capturing something lasting in this work.

The final images of the publication are the most arresting. The first photo shows sundown breaking through a smattering of lowered clouds above Nottingham’s suburban skyline. Television aerials, rooftops, and elm trees are shadowed outlines against the sky. In the second, PE! and Mutant emerge from a tunnel, their camera pointing skyward above the tall embankment walls. The autumnal evening light breaks through the surrounding oaks and sycamores, beckoning their momentary departure from the river’s world. The topography reminds us of the importance of seeking vantage points from which to explore our cities, both above and below, for it is here where we find glimpses of light amongst the pent cloisters dim.

Artists and writers continually make rivers a source of inspiration, long since Homer recorded Odysseus passing the River Styx in the Underworld on his journey home from Ithaca. Every other week a new book is published by an author on sabbatical on the topic of Britain’s lost waterways, exploring their contours alongside their own gushing personal narratives. Not to say that there are not diamonds in the rough, but often those who take the path less travelled present the most interesting work, simply by letting the territory do the talking.

Given the dire ecological state of Britain’s rivers today, in which sewage is pumped out at an alarming rate by water companies and only 14% of these meet good ecological standards, it is the continued efforts of activists, artists, and explorers to uncover these places and bring their findings to the shore, for positive environmental change and as acts of joyful creative documentation.

Today, the river people of Britain’s waterways have become sparse. PE! and Mutant inherit their lineage, dwelling in the margins, studying their environment, warning us of impending danger, pushing stories into mythologies, underground once more — exactly where they want to be.