Wir stehen bereit presents the actions of Zelle Asphaltkultur an unconventional ‘cell’ of graffiti writers. The work of the group is somewhere between graffiti and hardcore street art that obviously aims to provoke the viewer. This publication is as highbrow as graffiti gets. Inside there are six intellectual articles written by graffiti artists through to a cultural critic which are then followed by an interview with ZA.

The first article, written by Os Gemeos, is a brief description of some of the ideas behind the ZA group. They pose a number of questions regarding the place of graffiti, art in general and the public’s perception of it. As with the rest of the articles in the journal the text is written in German followed by an English translation. Later the graffiti writer Moses also makes a contribution with a week long diary of the imagined stream of consciousness of a German commuter. The commuter is exasperated at the work of some graffiti artists (ZA) he sees on his way into work and over the week rants to himself in outraged contempt. Finally on Sunday the commuter sees some trite piece of political satire on facebook and feels the world has been put to rights. The piece is quite funny and how I imagine the mind of the average Daily Mail reader works.

Elsewhere there is an article by Peter Michalski who I’ve come across before on the pages of Graffiti Magazine. He starts with a discussion of the place of graffiti and more specifically the work of Zelle Asphaltkultur within mainstream art. He then focuses on three specific works by ZA and examines the content, how they relate to graffiti, and how they were done. He ends with the suggestion that the group is at the forefront of the evolution of graffiti as we know it.

…radical political graffiti in Germany has a long history that goes back to a time of real and violent political struggle on the streets.

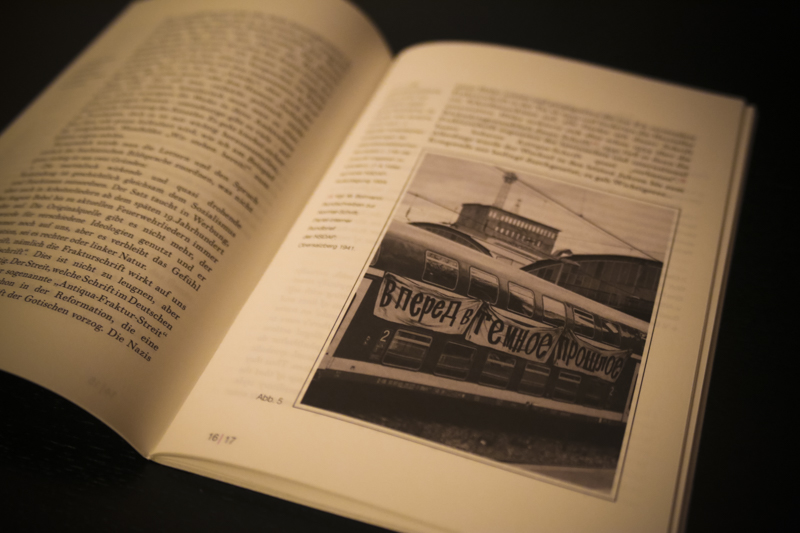

Next we come on to the artistic director Fabian Lasarzik who puts the work of Zelle Asphaltkultur into its creative and cultural context. He highlights the group’s political style that incorporates slogans and images of ideological movements in a deliberately vague way. He states that graffiti is “a kind of synanthrope of and a reflex toward the industrialization or the modern age with all its contradictions.” The article ends with a few historical facts about blackletter type that almost comes across as an attempt to prove that ZA aren’t a bunch of Nazis. Lasarzik recognises that “a great deal of provocation is at play here.” Perhaps unintentionally ZA’s choice of slogan in this particular type draws comparisons more generally to graffiti; what does particular writing mean to the reader, and how is the writer then politicised or racialised by that reader? This leads on to the cultural critic Lene ter Haar who discusses the publics reaction to the work of Zelle Asphaltkultur. She points out the placing of the graffiti and how internet users responded. One wrote a poem while another tweeted a picture.

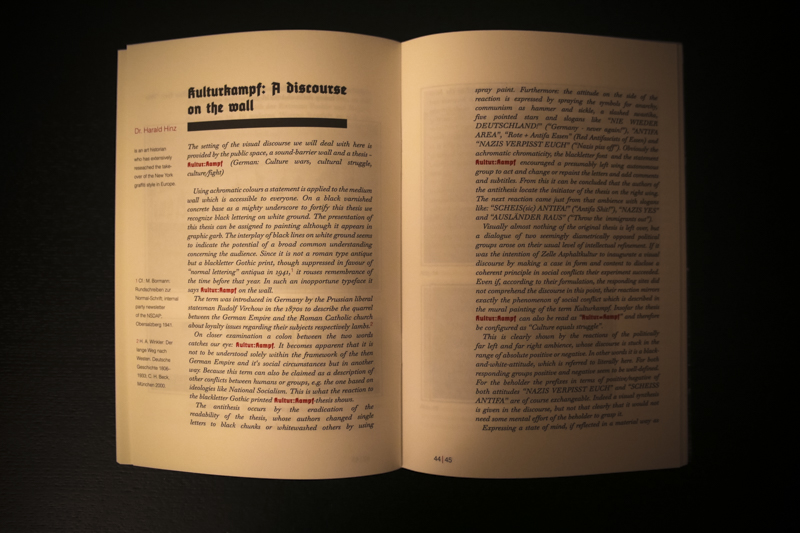

I’ll finish with the text by the art historian Dr. Harald Hinz who looks at Zelle Asphaltkultur’s Kulturkampf piece. Here they simply painted ‘Kultur:Kampf’ in huge letters across a wall. Hinz observes the apparently spontaneous reaction to it. This involved someone painting over the letters and spraying a range of left-wing symbols and clichés over it. In retaliation someone else then sprayed a range of right-wing slogans over that. Hinz dismisses the ignorance of these actions by people who fail to grasp the “visual synthesis (that) is given in the discourse”. Instead by resorting to graffiti they demonstrate “their usual level of intellectual refinement.” However the reaction to the original piece seems contrived. When does the hammer & sickle ever get put up alongside the Anarchist symbol? Why do the opposing ideologues only erase the original graffiti rather than each others? Also the same hammer & sickle and Anarchy sign appear over another ZA piece at the end of the journal too.

Besides, radical political graffiti in Germany has a long history that goes back to a time of real and violent political struggle on the streets. It seems hypocritical to dismiss it as unrefined when promoting another type of graffiti that, as Lasarzik points out, also grew out of the “neglected city areas and social issues” of its time.

From the magazine I get a sense of boredom with the conventions of graffiti and a desire to do something different by the Zelle Asphaltkultur cell. They have original ideas and do some proper hardcore actions. Overall the journal is an interesting read, nicely produced, and the few photos illustrate the text well too. However Wir stehen bereit does come across as a bit pretentious at times. The musings of art critics aren’t my first choice of reading and I found some of the over-complicated language unnecessary and hard to read. I don’t mean the odd long word but whole sentences the meaning of which were difficult to understand.