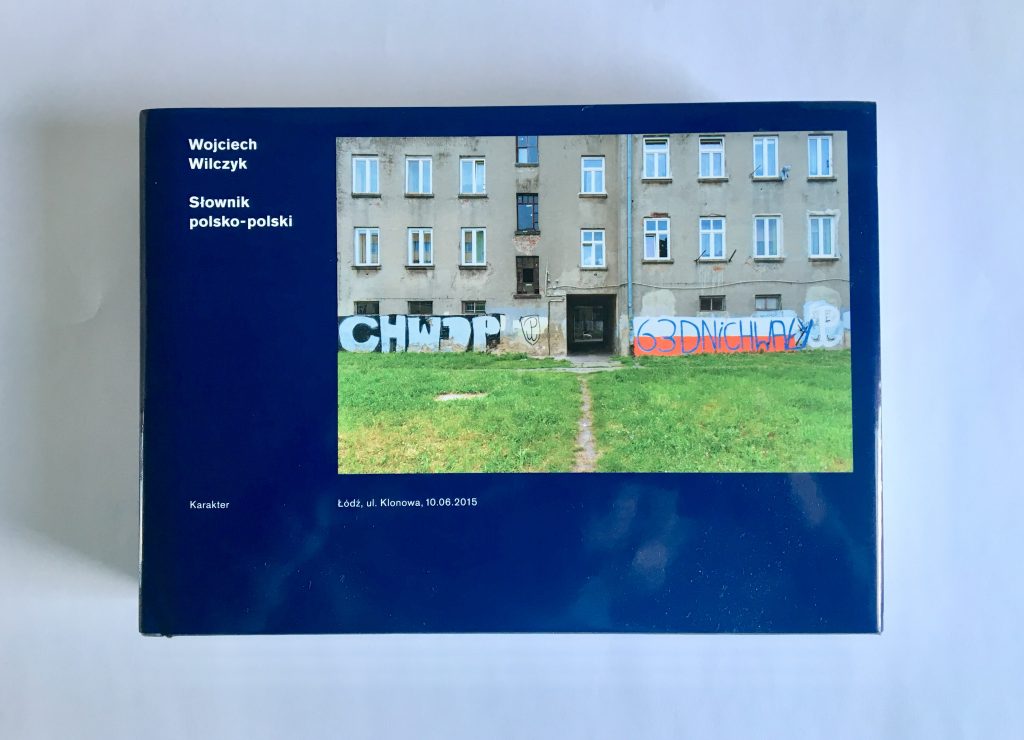

Having reviewed Wojciech Wilczyk’s work in the past the Graffiti Review were pleased to catch up and ask the photographer about his newest release Słownik polsko-polski, which translates as the ‘Polish-Polish Dictionary’. This evolved out of his previous book, named after the notorious ‘Holy War’ derby between the two major Kraków football clubs, which documented the graffiti of Polish fans. His latest publication focuses on the nationalist murals that have come to dominate the country’s walls under the PiS government.

the Graffiti Review: So, to begin can you just explain how the photography project behind your latest book came about?

Wojciech Wilczyk: It all started with murals on Kijowska avenue in Kraków, where you can see the figures of Pope John Paul II and General “Nil” Fieldorf, which I photographed for the Holy War series. After two years, the latter was repainted, so I photographed it again, and then involuntarily entered the phrase “patriotic mural” into the google search engine and received several dozen references to such projects. I was stunned and fascinated by it although, while taking photos for the Holy War in Łódź in 2013, I had come across football murals using patriotic symbolism.

The title, ‘Polish-Polish Dictionary’, refers to the translation of recent history from Polish into Polish, which is the case in murals painted by people who describe themselves as patriots. Looking at the political attitudes of contemporary Polish citizens, listening to opinions expressed by people with right-wing views, one gets the impression that when speaking Polish we are using different languages.

one gets the impression that when speaking Polish we are using different languages.

GR: The subject matter of the murals draws on a specific coterie of historical characters namely the ‘Cursed Soldiers’. Alongside these, often obscure figures, are painted well known twentieth century politicians such as Józef Piłsudski. What can these murals tell us about the current political climate in Poland?

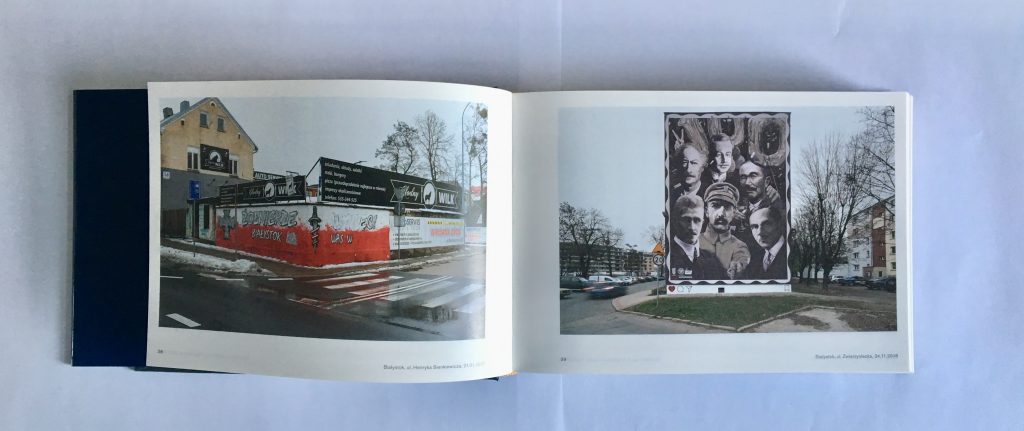

WW: Note that patriotic murals feature almost exclusively men (the only exception is the widely represented partisan nurse Danuta “Inka” Siedzikówna). White, heterosexual men, guerrillas, soldiers, insurgents, military commanders, kings, politicians, and Catholic church dignitaries. The nationalist Roman Dmowski and the autocratic Józef Piłsudski, are ideal synonyms of political strongmen, real tough guys. At least, that is how contemporary politicians in Poland see them, especially those from the ruling party.

GR: Yes it is very noticeable that nearly all the images painted are men. Although, aside from Inka, you do document a bizarre series of murals showing a yuppie playing football and computer games with a soldier from World War I. The figure of a modern woman appears alongside them quietly reading a book while in another scene she gleefully holds a rifle. What on earth is going on here?!

WW: Probably the author, a graffiti artist nicknamed NTKOVCA, intended to show that contemporary young people would behave in the same way as members of Piłsudski’s Legions as such a uniform is worn by the figure of a soldier painted on this mural or other fighters for independence in 1918. The writing stencilled alongside these figures says “100 years of independence / They were as we are / Can we be like them?” However, the question is would such a situation be possible today? In fact, the comic style of these murals, and the situations arranged on them, give the impression that this group was going on a date and not to fight for independence.

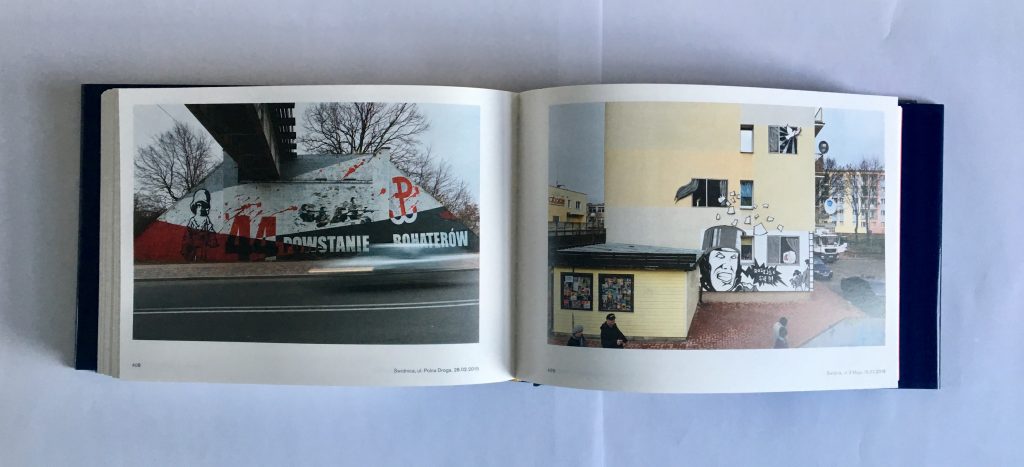

Anway, going back to your original question, the myth of the so-called cursed soldiers, which are seen as the only righteous oppositionists after 1945, was created for ad hoc political use by the Polish nationalist right. This was to eliminate the legend of leftist activists of the democratic opposition, whose actions led to workers’ strikes in 1980, the establishment of trade unions independent of the communist authorities, and, consequently, to the change of the political system in Poland in 1989. For football fans prone to stadium fights and illegal activities, figures of anti-communist underground guerrillas, such as Józef “Ogień” Kuraś or Zygmunt “Łupaszka” Szendzielorz, who commanded spectacular military actions, while also their subordinates murdered civilians, are attractive for several reasons. They perceive them as fanatical patriots, but also as extreme, ruthless people, acting in violation of the applicable or imposed law.

GR: Talking about football how would you describe the connection between fan groups and these new murals?

WW: About 50% of the murals in the book were painted by football fans. Already when I was finishing work on the Holy War, the process of legalising the operation of fan groups and establishing legally operating Fan Clubs, which therefore had to replace the slogans and characters appearing on the murals, began. The use of the symbols of independence, slogans and signs of the Polish underground state from World War II also has the advantage that such graffiti are not defaced by opponents from rival clubs. If the mural is damaged, only the club emblems are repainted.

GR: So the murals are actually serving the interests of different groups, for subtly different reasons, coalescing around nationalist imagery. How has the legalisation of the fan groups changed the design of their murals?

WW: The point is that at the beginning of the second decade of the twenty-first century, fan clubs began to be registered as legally operating associations by league teams. When their members decided to create murals, then in the situation of full legality, obtaining permits from the owners or administrators of the walls for the appearance of the paintings on them, they could not then paint slogans about the “superiority of the white race” decorated with swastikas or Celtic crosses. Painting the so-called the cursed soldiers, partisans with often extreme right views, participating in the National Armed Forces, is also a kind of naturalisation of this formation and nationalist slogans or symbolism (e.g. the NSZ cross resembling the Iron Cross) in the public discourse.

GR: The paintings here are a lot more polished and professional compared to those featured in your previous book. Aesthetically I do like some of the murals, for example the 1920 piece from Łomża, but generally I find the slick execution sterile. There are also jarring uses of imagery such as an imposing mural from Gdańsk executed in some sort of ‘Warhammer 40,000 style’. Michael Jackson alongside a WWII soldier is another weird juxtaposition.

WW: The mural referring to “Warhammer 40,000” was created by Rafał Roskowiński, who is very often employed to paint official patriotic paintings. The soldier from World War II, who looks to me like a commando from the British landing forces, is supposed to be the image of a Warsaw insurgent… I have no idea how he came to meet the famous pop singer, the child of a steelworker from Gary, Indiana. There was probably an empty spot on that garage wall, and that’s some explanation for the coincidence. In the book I tried to present the entire spectrum of the phenomenon, so there are murals painted by football fans (roughly half of the album) and more official ones, commissioned by local state councils, institutions or fundations. The former are painted by more or less talented amateurs, and the style is a mix of conventions and clichés from the dustbin of pop culture in the age of Facebook and Instagram – the effects sometimes resemble naïve painting. The latter, painted by professionals, i.e. people from art academies, refer to comic or poster stylistics, and sometimes to the propaganda paintings of totalitarian states, where a realistic convention is used to create allegories. Something like this was official in the art of the Third Reich, the Soviet Union, and Communist China, and is still used today in North Korea.

the style is a mix of conventions and clichés from the dustbin of pop culture in the age of Facebook

GR: There’s also a vision of nonlinear time represented in the murals whereby history exists in the present. For example there is a towering portrait of six historical figures reimagined in the present. They’re celebrating a hundred years of Polish independence, the central figure of Piłsudski holds a selfie stick and below are the like/comment/share instagram icons.

WW: This is supposed to be a kind of “update” of the glorious past, which also proves that the authors of such murals (in this case Jarosław Fabiś) do not cope well with the problems of the present … In fact, the politicians presented in this mural were in a strong conflict with each other.

GR: Finally, what has the public’s reaction been to these murals? I mean the images in rural areas of guerrillas fighting in villages must be pretty grim to live with and I do notice others have been defaced.

WW: There are very few cases of destruction. In the book you will find all that I have come across, and these repainted murals are then renovated, sometimes it happens several times. Major Zygmunt Szendzielorz “Łupaszka” or Józef Kuraś “Ogień” are most often attacked because the units they commanded murdered civilians, women and children, sometimes these were actions of pacification or ethnic cleansing. Probably the Three Arrows symbol painted on a mural in Kalisz indicates that someone from Antifa defaced it. Generally, patriotic graffiti has wide social approval, when people talked to me several times during the shooting, I always heard positive reactions.

GR: Okay, we’ll end it there. Thanks for this informative interview and telling us more about your work!

Wojciech Wilczyk is currently working on the project “Wdzięczność / Благодарность” (Gratitude), which is a documentation of commemorations at war cemeteries and Monuments of Gratitude to the Red Army. The emblems of the USSR, the red stars, and the hammer & sickle as symbols of the totalitarian state are now removed from these objects. The content of the commemorative plaques has been changed, many monuments (mainly those of gratitude) are demolished, and there are also frequent acts of vandalism. His work can be checked out at the hiperrealizm blog.