To give it its full title Boulevard: On Trespassing and Culture is a great project, conceived by Thomas Lauterberg alongside editors Robert Kaltenhäuser and Harald Hinz, which was launched last year. The aim of the publication is to collect and reprint hard to find essays alongside translated texts previously unpublished in English. Boulevard is foremost a critical and art-historical endeavour presented as a midi format newspaper with three distinct pull-out sections. The first of these is a short current affairs section of graffiti news and reviews, in the middle are the reprinted essays, and finally a paper filled with striking images.

The introductory pull-out begins with a few nice reviews such as Stencibilty; the “anarcho street art event in Tartu”, the Russian book Buffantgarde, and the ‘Graffiti Now’ edition of Kunstforum International. Events like the Unlock bookfair, Tag Conference, and CityLeaks festival in Cologne are also promoted. Finally there is a review of the Urban Art Biennale in Völklingen and an interview with its curator Frank Krämer. In between is a whole page given over to an image of the fantastic work Only God Forgives by the Berlin collective ‘Rocco and his Brothers’.

It’s the following section which is what really makes Boulevard an exciting addition to the burgeoning graffiti publishing scene. Here are the reproduced essays and texts from various out of print and rare books. The first of these is a piece about art and the growth of graffiti originally written by Allan Schwartzman in 1984. Despite being over three decades old this is a great read and the analysis remains spot on. The essay charts the art establishment’s relationship to art in the ‘streets’, and how it reacted to graffiti in New York. Schwartzman picks apart the class dimension in this relationship whereby the darlings of the street-art scene “understood that using popular culture as both source and target was a choice (unlike the graffitists, for whom popular culture was the available visual language)”. Meanwhile the graffiti writers who managed to make the reverse cross-over into the art world were left producing mere “souvenirs” of their former illegal work.

Hoffman rejects the cave-man-as-graffer origin story and instead premises the roots of contemporary graffiti in the development of capitalism and the modern state.

I’ve read quite a few texts that consider what made graffiti public enemy number one but less so what made it an art form. Schwartzman chooses language that describes graffiti as a creative cultural phenomenon rather than a crime rampage. He describes New York kids in the 70’s who “formed writing groups” to work together and compete in style and substance. The image conjured up is more akin to an informal art school than the usual one of a violent neighbourhood crew. When he says that “already a lot of mediocre artists have jumped on the street bandwagon and are doing things outdoors that mean as little as they did indoors” he could easily be talking about the present day. He ends the essay with a note of premature nostalgia, imagining the end of graffiti as it was, not predicting what it would become.

The other substantial chapter is Detlef Hoffmann’s, 2000 Years of Graffiti or Each Age has the Walls it deserves, originally published just a year after Schwartzman’s text. Hoffmann begins, with what continues to be a standard trope of art-historical writing on graffiti, in the time of the cave man. In graffiti historiography cave paintings are used to highlight the innateness of the act but this actually draws on a classist and racialised discourse around the ‘primitiveness’ of the modern graffiti writer; the dog marking its territory becomes the Neanderthal wielding a spray can. However Hoffman rejects the cave-man-as-graffer origin story and instead premises the roots of contemporary graffiti in the development of capitalism and the modern state. More precisely the “civil public” and, much later, photography created conditions in which graffiti has cultural significance. Spanning two thousand years Hoffman discusses the classic lovers’ names enclosed within a heart, ancient graffiti found on the pyramids, eighteenth century Spanish names from Utah’s Glen Canyon, Pompeii, and, as the article was written in the mid-80’s, even Zurich’s Harald Naegeli gets a mention.

Kool Killer is crappy in many respects yet it seems to be the perennial favourite of every academic who’s ever chosen graffiti as their topic.

A more recent essay is Oliver Kuhnert’s Aesthetic Poverty and Egomania which, translated from the original German, first appeared in The Death of Graffiti book. He argues that graffiti is a reproduction of capitalist individualism rather than the social rebellion its practitioners often claim it as. Graffiti writers are trapped in a contradictory stance whereby they engage in strict internal policing of aesthetic standards and rules of expression, while at the same time feel they are breaking conventional codes of behaviour. Their creativity is rigidly conformist and exists between the anarchism and totalitarianism of what Kuhnert terms “the two poles of graffiti ideology”; a horseshoe theory of graffiti if you will. In its original incarnation Kuhnert’s text was a statement to which other contributing essayists responded and it would be nice to see some of these in future issues of Boulevard!

Also included are essays that cover graffiti as a ‘sport’, an early work which surveyed the geography of gang graffiti in Philadelphia, and the biblical sounding In the Beginning There Was the Word. In his essay, a call for artistic innovation, Kaltenhäuser takes a shot at Jean Baudrillard’s Kool Killer. Originally written in 2009, surprisingly, this may be the first critique the French sociologist’s essay faced. I mention this because Kool Killer is crappy in many respects yet it seems to be the perennial favourite of every academic who’s ever chosen graffiti as their topic. Ralph Beuthen takes Baudrillard to task more exhaustively and, despite believing he still presents a “very interesting argumentation”, cannot help but broach the fact that his essay’s littered with “tenuous points, inconsistencies, simplifications and exaggerations.” Although, to be fair on Baudrillard, I did recently read an article that put his ‘empty signifiers’ in a different light.

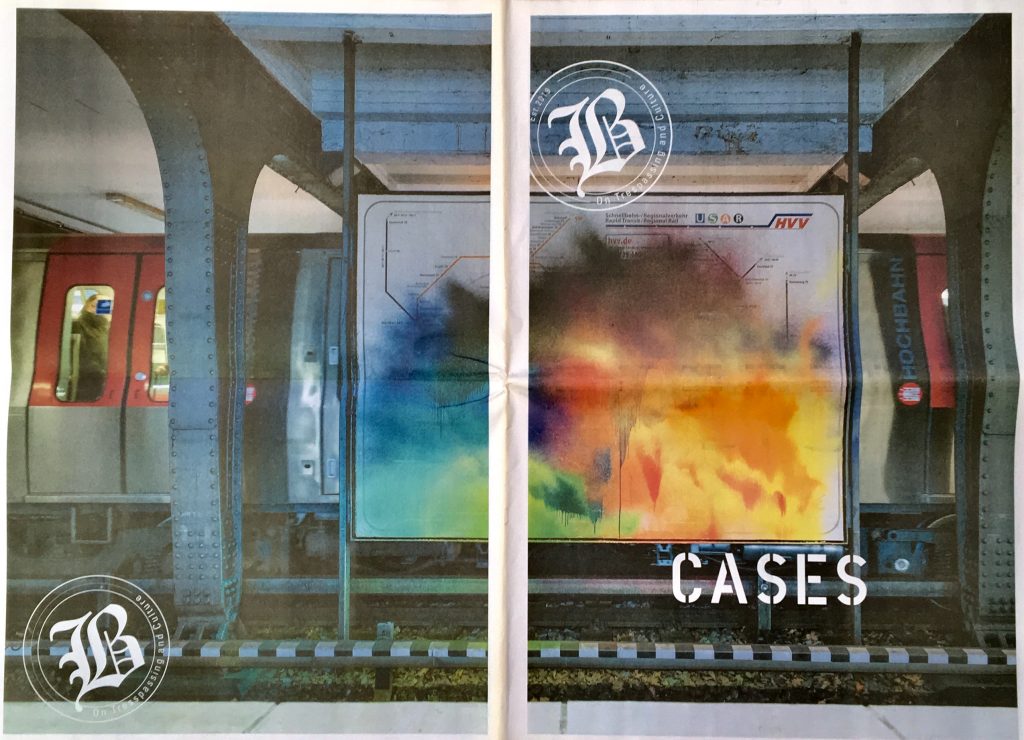

The final section of this sophisticated newspaper is a showcase of various art projects and exhibitions. None of the images featured show conventional graffiti forms but are more like avant-garde graffiti interventions. Photographs by Tony Klicklack, a series by Gen Atem and Miriam Bossard, and images from the exhibitions of Aris and Tocka alongside Edward Nightingale with Moses & Taps™ are all presented in a nice format. The second volume of Boulevard, which is soon to be published, will feature several more interesting interviews, exhibitions and projects. Readers can also look forward to reprints of texts by Patrick Hagopian, Lene ter Haar and Orestis Pangalos to name but three. Judging by the first issue, Boulevard looks set to be an indispensable publication for those with an interest in graffiti culture, theory, and history.