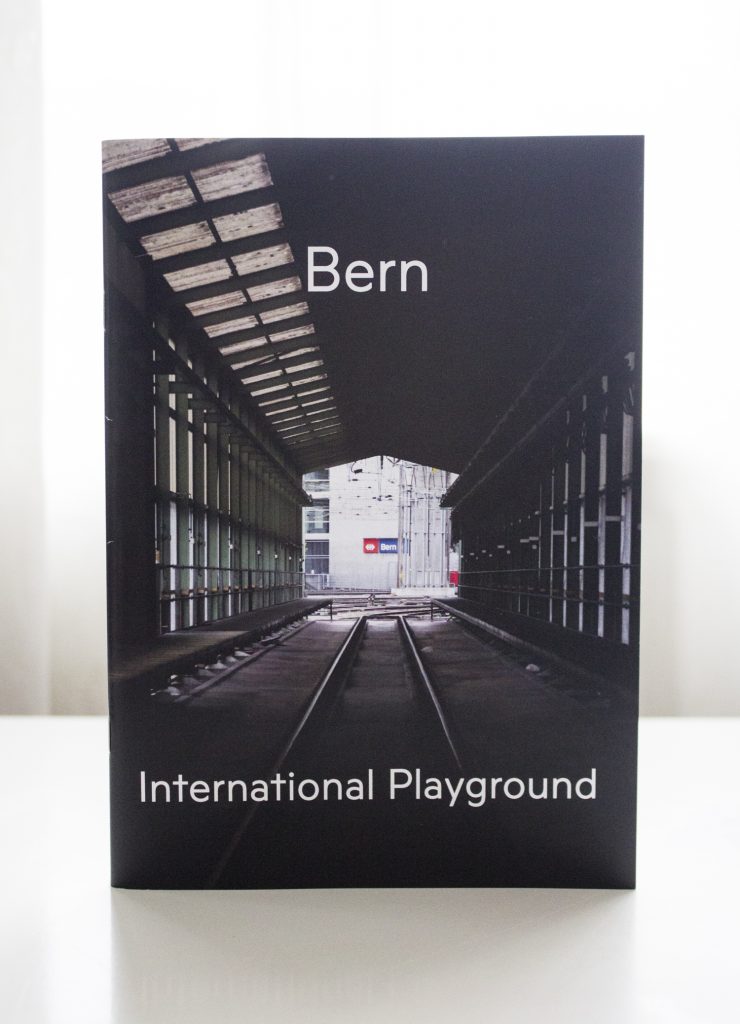

Bern: International Playground is a quirky new zine from Switzerland. One way to describe it is as an almost scientific catalogue showing samples of graffiti found in a particular environment. The photographic survey presented in this format is the result of more than a decade of research into vandalism occurring on Bern’s S-Bahn trains. From the start, the empty frontcover subtly evokes the concept within as the zine concentrates on the often overlooked margins.

At first glance Bern could be mistaken for a bit of a gimmick and it is introduced in a light-hearted way as a trainspotters game to spot who’s who. Trying to relate it to anything else the nearest I could think of was the Where’s Wally? series which apparently fit into a genre called wimmelbilderbuch. In ‘Reading as Playing‘ Cornelia Rémi argues that these type of books are a form of play in which “readers are constantly encouraged to question their own impressions and former hypothesis” about the content. Bern is very similar in this respect. It contains a hidden narrative thread which makes the reader imagine what’s not shown, and the story or action behind it. The subtitle, International Playground, is an ironic reference to the fact that, despite its low-key status, Bern has attracted hundreds of foreign writers to its system. This subtitle also nicely links the playful concept of the publication to the performative act of graffiti writing itself.

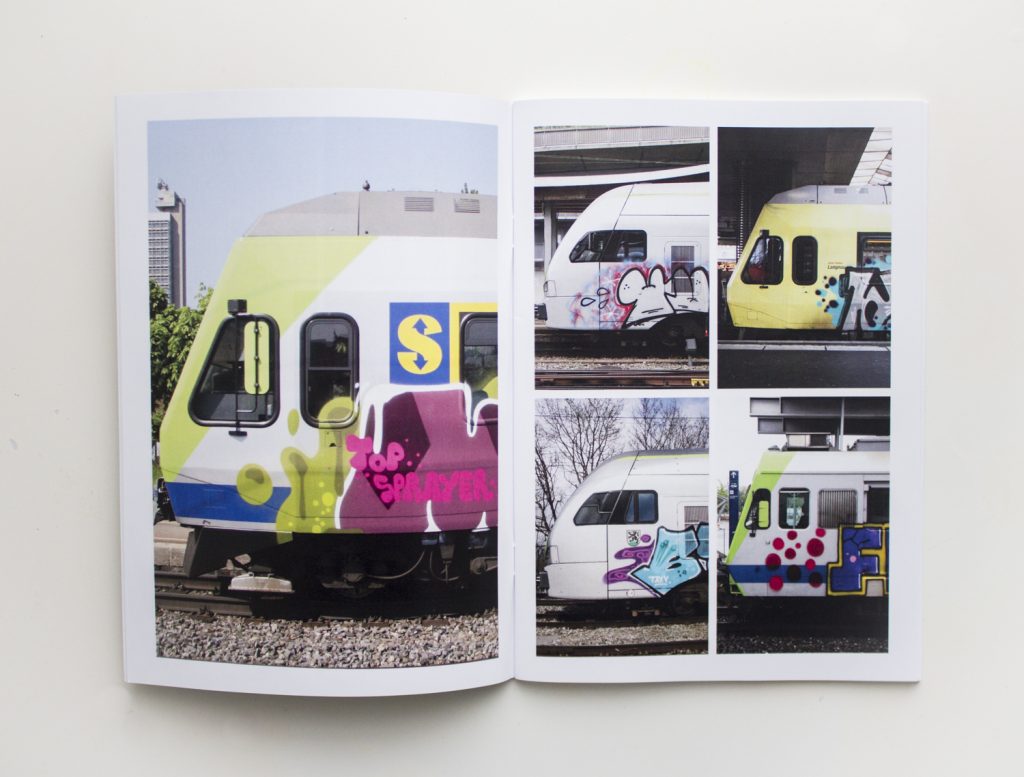

The real focus of the zine is on the periphery of the graffiti piece. Rather than concentrating on the style of the lettering the reader has to consider the often overlooked margins. This concept can be related to the study of the borders of books; called marginalia. Historians sometimes look at the notes made by readers, or the images drawn by a medieval monk around a text, to get new insights. Marginalia can be rare evidence of what was on the mind of someone in the past. If modern graffiti is viewed as writing, placed on a surface other than a book, then these borders are also an interesting way of accessing the ideas of the writer. In an artistic subculture where letters form the art and words function as icons, Bern highlights overlooked details. The most simple bits are signatures, dedications, and dates. Some of the writers leave clues about where they’re from; Spain, Greece or Holland. Others show how they view themselves; as Radicals, Bandits and Chrome Gangstaz. Alongside threats and challenges to the police are insults to train drivers. There’s also funny additions such as a speech bubble coming from the drivers cab, a farting letter, or a wheelbarrow of bricks that have been used as a fill. The marginalia here is mainly made up of classic graffiti symbols such as arrows, crowns or the peace sign alongside bubbles, clouds, drips and of course some cool characters.

Bern isn’t just a playful look at graff. As the standard format of graffiti publications doesn’t really change much it’s a serious attempt to present and explore the subject in a different way. The author also adheres to an unwritten rule not to publish pictures of other peoples work. So the zine is a methodical record of the periphery of graffiti on trains but also a slight criticism of its current representation on the internet and in magazines. The collection of photos presented in Bern has taken many years of work and the result is an unusual and good quality zine.