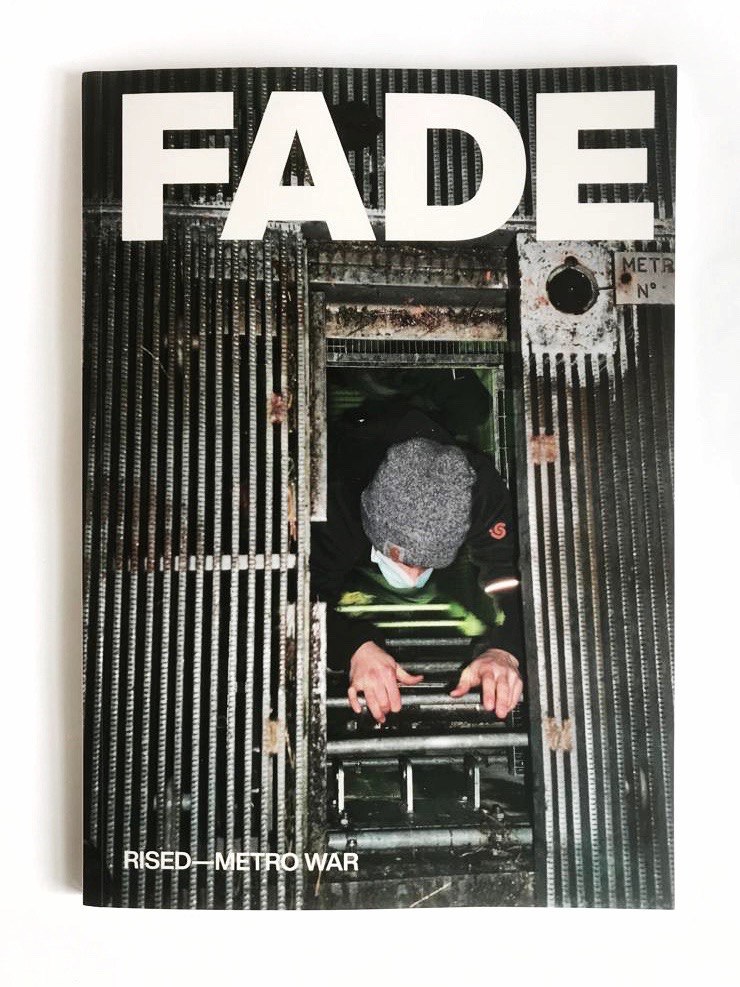

Fade is a new magazine produced by Backyard Parking, a self described ‘street culture’ publisher based in Milan. This initial issue, in Italian with an English translation, revolves around a single writer, Rised, and their personal ‘metro war’. Now, before going into its content it’s worth mentioning just how nicely produced this publication is; the magazine feels quality, with nicely sized images, and well edited content. The first half contains a sort of informal interview interspersed with various photographs of trains alongside associated actions and paraphernalia. Meanwhile the rest of the magazine is given over to trains from Italy and beyond that have been given a fresh coat of paint by the artist in question.

The magazine begins with a brief manifesto stating the intention of the publishers to reclaim overlooked elements of street culture and, more specifically, focus on individuals in order to avoid “a stereotyped representation of writing.” Following this begins an interview conducted between Rised and an unnamed interlocutor in a conversational style, as if holding a private conversation. The dialogue starts off introspectively with Rised discussing his own graffiti philosophy and making astute observations. Of his artistic development he remarks that “you never feel like you’ve arrived, in style I mean. There’s always that extra something you want to do.” Which is a position a lot of writers could probably relate to.

The conversation then meanders through an interesting discussion of the practicalities of painting trains vis-à-vis walls and street bombing, and how the related time pressures affect technique and style. One interesting point that Rised discusses is social media and the effect on how graffiti is viewed. While they accept that it allows exposure on a scale that kids pioneering graffiti back in twentieth-century New York could only dream of, Rised still feels it is denigrating the graffiti. It’s understandable that, alongside draconian policing, the constant avalanche of images now online can cause people to desire more privacy and ownership over their work. Rised states that sometimes they’re even happy when a piece gets buffed before anyone else gets to see it; the graffiti is left only as a private photo.

Rised also criticises the typical badly angled photo of a graffed-up train.

In his book, The Social Photo, the social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson argues that the experience of the passenger in the nineteenth-century train anticipated our contemporary use of social media and consumption of images. As passengers were able to travel in relative comfort at unprecedented speeds the landscape they passed through was reduced to a panorama. The world was viewed through the technology of the train in a similar way to how we view it through our phone. Jurgenson describes how “the images in their proliferation and rapidity create an emergent stream in aggregate, and for the person doing the swiping, there is a more panoramic view of social life, akin to the montaged scenery from the train window.” So, while Rised decries the amnestic proliferation of graffiti images on Instagram, it’s an interesting idea that this way of viewing graffiti can be understood as a mode of observation brought on by the invention of train travel itself.

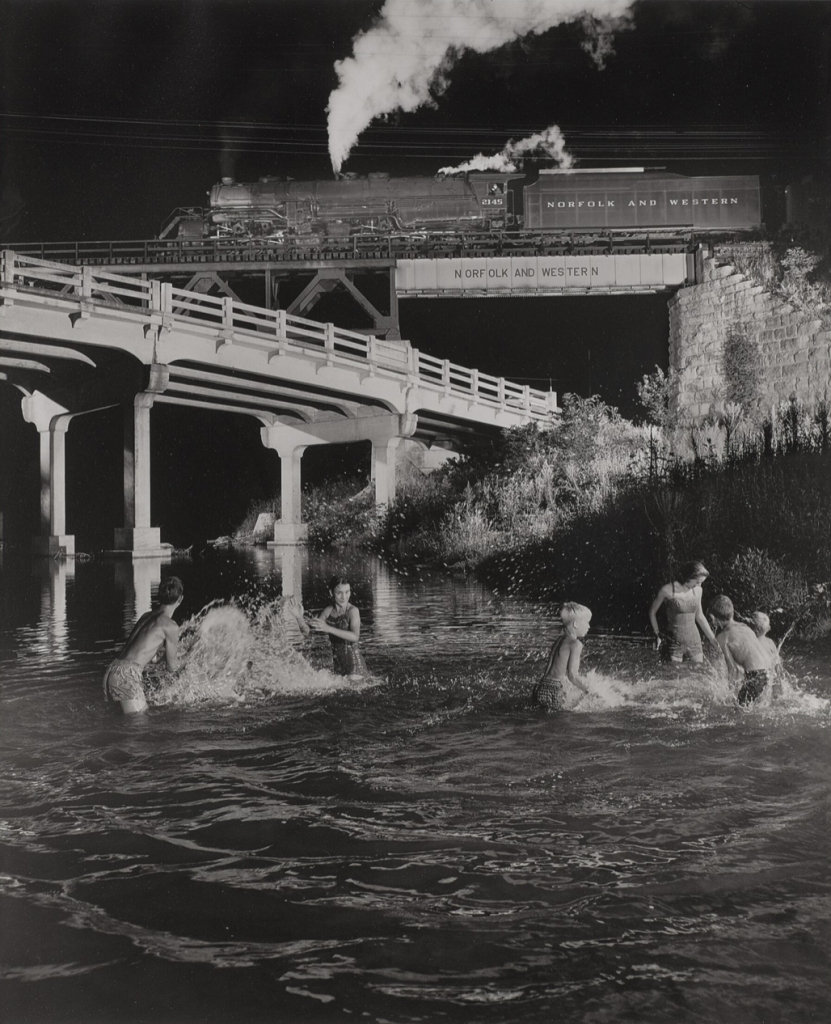

Rised’s other insight into graffiti photography revolves around the angle at which pictures of graffiti are often taken. In the mid-twentieth century the American railway photographer O. Winston Link derided the commonly composed ‘wedge shot’ whereby the front of a train would be captured at an angle in the foreground with the rest of the train disappearing into the background. Instead Link composed his photos to picture the train in its social and cultural context. His creations include Hester Fringer’s House, an image of a 1950’s American house interior with a locomotive thundering past framed by the living room window, and Swimming Pool, foregrounding bathers relaxing by a pool as a steam engine streams past in the background. Echoing Link, Rised also criticises the typical badly angled photo of a graffed-up train. Instead the correct shot should be dynamically framed at a slight tilt rather than face on at a 90° angle. The ideal photo for Rised is one in which the train can be seen displaying both graffiti and its context, such as “a well taken photo of a train on a bridge”. A nice example of this sort of contextualisation is reproduced in Fade as a double page spread showing a train standing at Cologno Nord which has been taken from a height showing both the foreground, station, and a park and buildings in the background.

Anyway, the conversation between Rised and the anonymous acquaintance continues with a variety of topics from the experience of the police, to philosophical questions of ethics v’s the law, public/private space, protest, and personal ambition. Following this in depth discussion there are twenty-five pages displaying Rised’s carefully framed photographs. This initial edition of Fade is a great magazine so I was pleased to find out that the publishers are planning to make it a biannual release. Future issues will also focus on a single writer with an emphasis on people and experiences. So, expect something a little different in future issues!