Graffiti is a new collection put together by Friederike Häuser which, as its German subtitle suggests, seeks to provide a range of contemporary and interdisciplinary perspectives on the topic. In his forward to the book Jeffrey Ian Ross explains that the publication is one of an ever increasing body of contributions there are on the subject. Containing fifteen chapters, ranging across diverse topics, I’ll just focus on those written in English.

One of my favourite contributions was by Ulrich Blanché who investigates the influence of punk stencils on the evolution of early letter based graffiti in Europe. He seeks to challenge the accepted narrative that graffiti writing was purely a cultural import from the US, pre-packaged for a European audience as a pillar of hip-hop. In fact, he argues that in many cases it was actually the punk scene which fostered the spread of graffiti from New York. As graffiti was popularised, pre-existing punk graffiti cultures were incorporated into the new movement. Blanché does mention tagging and political slogans as part of the visual output of punk but he mainly focuses on stencils and how their use interacted with the new graffiti. He highlights some notable examples of punks utilising stencils within the new subculture, however such stencilling was generally scorned because it suggested a lack of skill. Blanché argues that, rather than a lack of skill, the stencil represented what graffiti had been, so their rejection worked as an affirmation of the new graffiti subculture.

The relation of graffiti to hip-hop can often be a heated debate because, when the pairing is challenged, it often extends to the personal and cultural identities of graffiti artists themselves. This problematic deconstruction of graffiti is what Jacob Kimvall addresses in his chapter. Instead of trying to wade in on exactly where graffiti stands in relation to hip-hop he looks instead at why graffiti is hip-hop. An interesting argument he makes is that graffiti, alongside breakdancing, acts as something of a cultural bulwark to the commercialisation of other elements of hip-hop, in particular rap. Whatever its origins Kimvall ultimately concludes that graffiti should be understood as a part of hip-hop and wonders why it is that more studies of graffiti aren’t made through this lens.

…it was actually the punk scene which fostered the spread of graffiti from New York.

Meanwhile, contrasting it with rap, Robert Kaltenhäuser frames graffiti as a universalist subculture that dismantled racial divides. The original graffiti writers created a movement that was inclusive, in opposition to the society they were living in. Kaltenhäuser argues that the subsequent racialisation of graffiti was done by cultural critics projecting their biases about primitive art onto the young graffiti pioneers. From there his essay then morphs into a defence of freedom of speech in which urban-art is anti-establishment trolling. The Frankfurt School, critical race theory, identity politics, and cancel culture are all thrown in. In general such terms are often used in reference to Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory and, when it comes to opposition to so-called political correctness, my suspicion is that this frequently amounts to little more than ‘why can’t I be racist anymore?’ In fact this is soon confirmed by a quote from Slavoj Žižek who says that he, for one, enjoys making racist jokes. Well, fine, but don’t squeal about freedom of speech when someone uses theirs to tell you to fuck off.

Ultimately Kaltenhäuser isn’t defending racism but the right of artists to be controversial. However, while freedom of expression may be a lofty ideal of the art world it relies on the safe space the gallery provides. Kaltenhäuser claims that graffiti is “the go-to method for the rebel with a message not deemed appropriate by the channels that be”. In fact, when painting in public spaces the result is often the rapid erasure, or ‘cancelling’, of the graffiti-artist’s work. Graffiti has never been a precious art because ‘cancel culture’ is when someone comes along and takes you out!

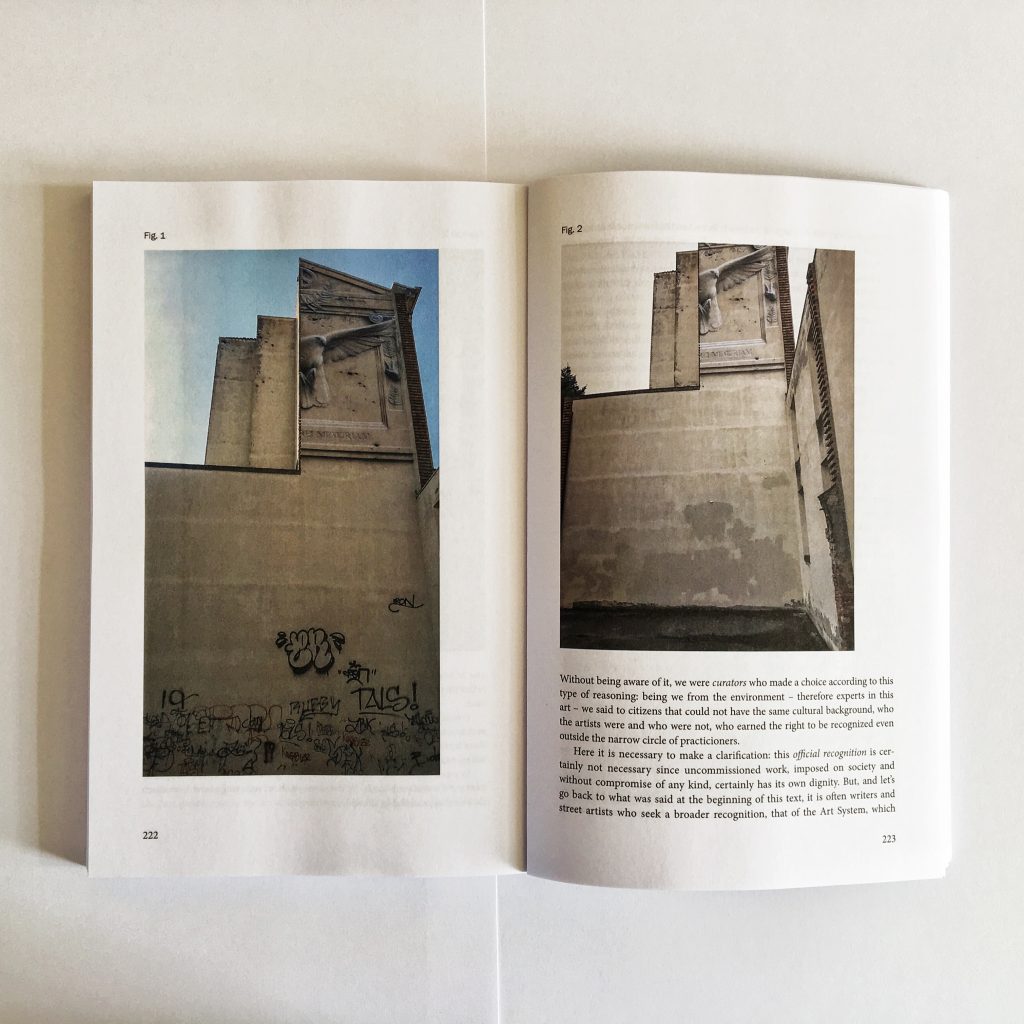

Pietro Rivasi also highlights censorship but this time the very real moral policing of graffiti as a symbol of crime. He sets out to tackle how such work can be re-presented as art, to a generally hostile public audience, within art institutions. After defining what he means by the terms ‘urban-art’ and the ‘Art System’ Rivasi questions the value of applying conventional criterias of art criticism to the former by the latter. This is a worthwhile approach because it’s frustratingly common for academics and art institutions alike to dismiss graffiti and street-art without a proper understanding of it. Rivasi’s chapter builds on what he has previously argued; for an understanding of graffiti as a clandestine art practice, rather than a style of painting. Graffiti and Street art, when transplanted from the street to the canvas, lose their basic essence and to maintain this it is “the documentation of the performance itself” which needs to be produced for galleries. Presented in this way a different story can emerge to challenge the viewer’s perception of both graffiti and the institution of art.

Katja Glaser also emphasises the action of doing graffiti, arguing that academic studies need to decentre the image. This sounds a kinda odd position to call for when graffiti is surely all about the image produced…? Well no. Glaser argues that graffiti is actually made up of the events surrounding its production. Rather than the image, she focuses on the importance of walking, and the discovery of the city. Like the Situationists who came up with the derivé, Glaser writes that graffiti practitioners share a deep knowledge of the city as a result of their urban meandering. To demonstrate this she uses the example of a line of paint that she found dripped across several miles of the streets of Cologne. She speculates that the line was created by a graffiti writer, who she then traces around the city using the artwork.

Based on the chapters highlighted above, Graffiti is an interesting book with a variety of different ideas knocking around. What they all seem to share is a critique of how graffiti is constructed; how it was created as a subculture, as part of hip-hop, or as an art. Despite Glaser’s call “for a detachment from an image-centred discourse”, the book has some nice illustrations too.

Thanks for the review, happy you read my essay, hope you found it worth..!

P.

It’s a shame that not all articles are translated to english….