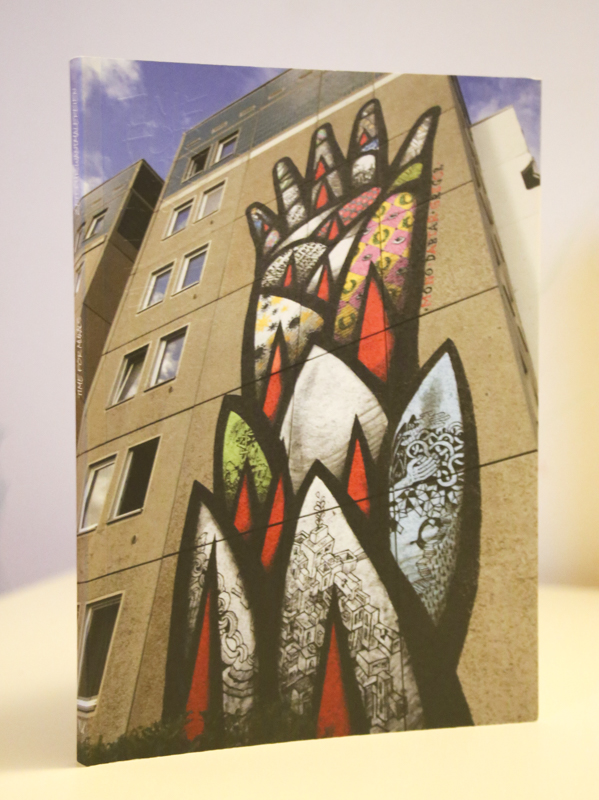

I recently got sent a copy of a book called Time for Murals. The book was published after a conference, organised by the artist Jens Besser, that took place a couple of years ago on the subject of the “contemporary phenomenon” that are urban murals. Now murals aren’t my usual area of interest but in my home town of London there are a few cool murals dating from the late seventies and eighties that I really like. The sort of murals that I see going up nowadays all seem to be large scale pieces of street-art rather than the community focused and often politicised murals that came before. Anyway as Besser points out in the book “a narrow interpretation may result in nerdiness”. So, as not to be classed a graff-nerd, it’s probably healthy to delve into another type of urban art that isn’t usually graffiti and doesn’t have to be street-art. Each chapter in the book is written by different artists and organisers discussing the place of murals in the city and within the urban art scene, descriptions of mural festivals, community initiatives, a bit of mural history and finally an interview.

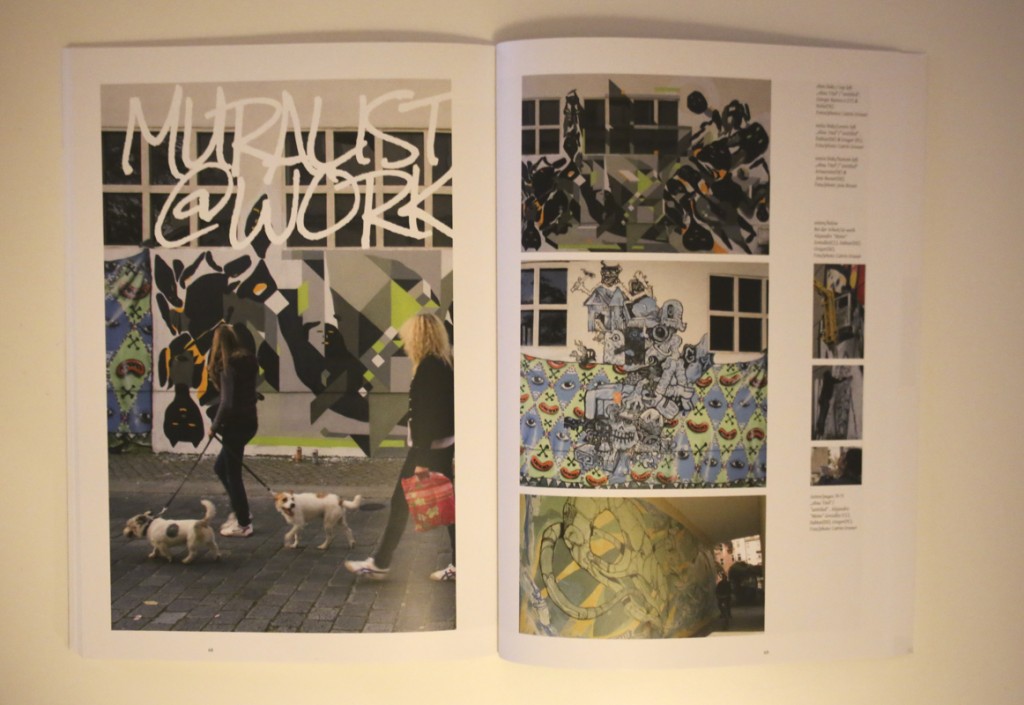

A few themes came out of the book that I found really interesting. One of these was the position of muralism vis-à-vis street-art and graffiti. Javier Abarca kicks off this discussion by comparing street-art to large scale commissioned works and “the mural festival”. He suggests that as street-art has become mainstream there is a shift away from pieces that are contextual and interact with their surroundings. These pieces reflect local culture, are usually painted at street level and are limited in their lifespan so that they fade into the everyday experience of passersby. However this type of art is being replaced by the sort of “monumental” works, often done by outsiders using cherry pickers to go beyond the street level, that are detached from their surroundings and could be found in any city. Away from the streets Pietro Rivasi notes the transformation of many mural festivals as a way of showcasing the work of illicit artists into commercialised events featuring professionals who ‘borrow’ the walls for a week. He believes the situation has helped street-art to become acceptable at the expense of graffiti which is seen as its negative opposite. However Rivasi says it should be understood that street-art has its “origins deeply rooted in writing letters and are often labelled as mere examples of vandalism.” In fact Abarca concludes his piece by arguing that the polarised relationship between graffiti and street-art has been effectively used by developers and city planners in gentrifying urban areas. Such relationships to government institutions is also something discussed quite a bit in the book.

Early on in the book there are some descriptions of how murals were utilised by the communist government in East Germany. They used them to project an idealised image of socialism on the city. Since the fall of the wall some of these sort of murals have been preserved but the painting of murals has gone out of fashion. Besser draws on the history of mural production in East Germany to call for better funding and support from local authorities. He also thinks that the practical skills to do murals should be taught in art schools as they were in the past. However he’s also concerned that artists should be able to challenge the mainstream and not become too controlled by the authorities. Two chapters in the book actually discuss successful independent projects that are supported by the authorities. The first is a month long festival called Bien Urbain that is held annually in the French town of Besançon. The organisers emphasise the local focus of the festival which aims to be site-specific and involve the residents of the town. A slightly different project is the Urban Forms Foundation which operates in Łódź in Poland. There the aim is to change the image of the city and give it’s residents free access to art on a daily basis. The long-term project has invited well known artists from around the world to participate and the organisers are conscious of how the murals are viewed by the public.

However not everyone trying to paint murals find the authorities willing to engage. The organisers of the Icone festival held every year in Modena have become disillusioned with the “absolute lack of willingness to explore the theme of urban art, the equally miopic inability to value already acquired assets by the city and finally the cultural policies and urban planning that (they) absolutely do not agree with”. Unlike the people who do illegal graffiti muralists often have to co-operate with and navigate around different state institutions and interests. Government authorities can be in favour of murals but at the same time are concerned about what message or image is being put across. Urban art sends a message out about who is in control of public space and it shapes how people perceive their surroundings. The sectarian murals in Northern Ireland or the walls painted in some Polish cities by football hooligans are examples of unsanctioned work that projects an image that the state doesn’t promote. As Denise Ackermann and José Segebre point out it is often illegal work that can actually resonate most effectively with the viewer. Another example could be Berlin which is covered in illegal public art which creates an independent image of that city. In her chapter Joanna Stembalska actually argues that such murals should be used “as one among many tools in constructing bottom-up activities.”

Throughout the book there are different opinions on the place of murals. It is argued that the murals discussed are having a positive effect on society, on how local communities view their cities, and even on the architecture itself. Although there is not a clear consensus in the book on the positive bottom-up role of muralism. One contributor David Villarroel says that the residents of the city he worked in lacked any art education which had a negative effect on the art he “brought into the neighbourhood.” Elsewhere, in contrast to what many of the other contributors suggest, Georg Barringhaus believes that the commercialisation of urban art has had a positive effect. The book throws up few of these sort of contradictions which reflects the tensions within urban art in general. The relationship between the legal and illegal, the extent of institutional involvement, the role of the community and the muralists themselves. Although a lot of the practicalities concern legal or commissioned murals I think much of the theoretical discussion surrounding who views it, how it shapes the visual urban environment, how murals are used by different organisations and for what ends can also be applied to graffiti, street-art and urban art as a whole.

I found Time for Murals a really interesting and engaging book. It is well produced with a sophisticated design and a layout that flows along well. My impression from reading it is that muralists often position themselves in a space somewhere between illicit graffiti and the kind of street-art that is fully institutionalised. There is an overall positive message that while modern cities are planned on large scales in which residents have little or no input, the ‘new muralism’ can be a way for urban communities to effectively shape their surroundings.