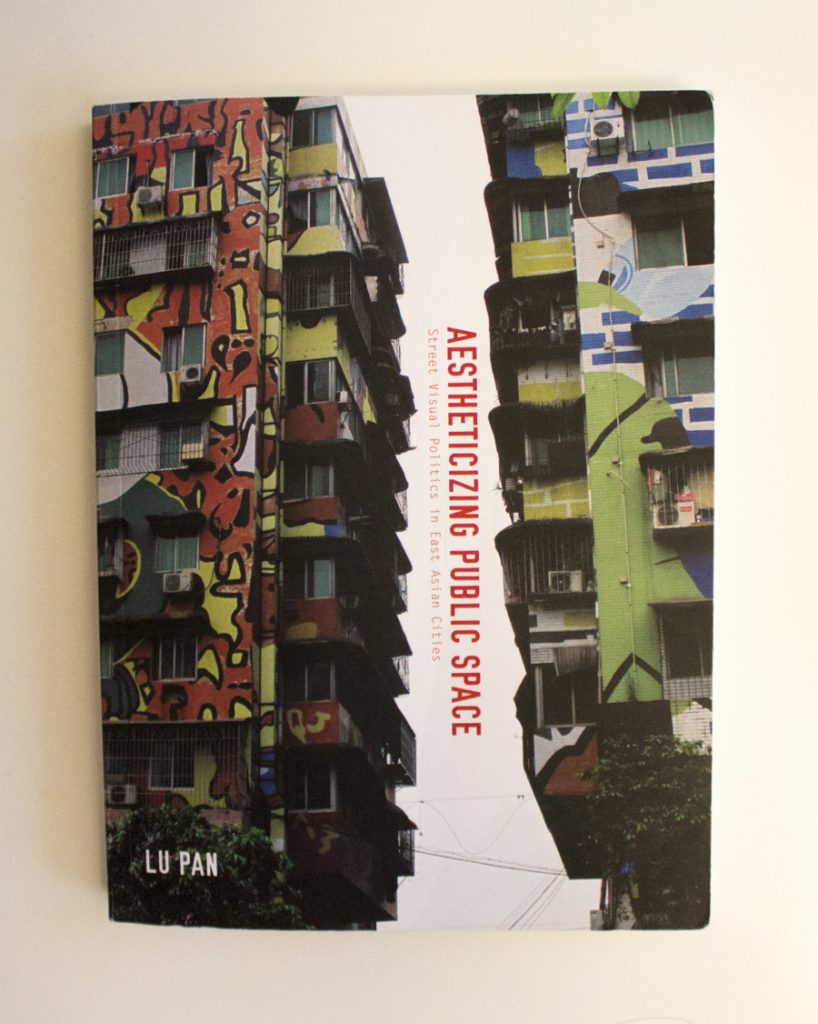

This latest post reviews Aestheticizing Public Space by Lu Pan which was released at the end of last year. The book studies graffiti in cities around East Asia; that is Hong Kong, China, Japan and South Korea. Lu Pan works with a broad definition of graffiti that includes everything from conventional graffiti letters, street-art, digital media and even traditional East Asian writing practices. There are four main parts to the book which each focus on different case studies of graffiti and discusses them in the particular social, political, or cultural context they took place. There is also an informative introduction and a ‘special’ fifth chapter of interviews. Lu Pan also sets out four topics for the book; carnival, publicness, aura, and the creative city. However here I’m going to focus on a few themes that crop up throughout the book which stood out for me. In particular there is discussion of the different views and approaches to graffiti in East Asia compared to in the West. Another interesting thread is the relationship between graffiti, public space, and the state. Finally Lu Pan also uses philosophy as a way of explaining and interpreting her subject.

So, I’ll start by mentioning the introduction which is actually a fascinating background to the place of public writing in this part of the world. First Lu Pan explains that she’s attempting to explore wider issues through graffiti. There is a brief history of modern graffiti which “celebrates the carnivalesque humour and disorder that is experienced by people in their daily lives.” Following that are individual segments on the politics and history of East Asian countries in relation to graffiti. It soon becomes obvious that, while in the West graffiti is commonly viewed negatively, in East Asia this is not always the case. In some countries such as Japan there is an existing tradition of wall writing that stretches back from ancient religious worship to Anarchist slogans painted during the Second World War. Likewise in China there’s also a tradition of wall writing but it is linked to state authority and power. Again this is a very old tradition that has survived in some form up to modern times such as when it was used as an instrument of propaganda by Mao. Although these traditions may be a very different form of writing to contemporary graffiti they can still inform how an observer interprets the graffiti they see on the street nowadays. In fact, later in the book, the writer Zyko says that when explaining to interested passersby he relates his graffiti to traditional letter writing (shufa) to make it understandable.

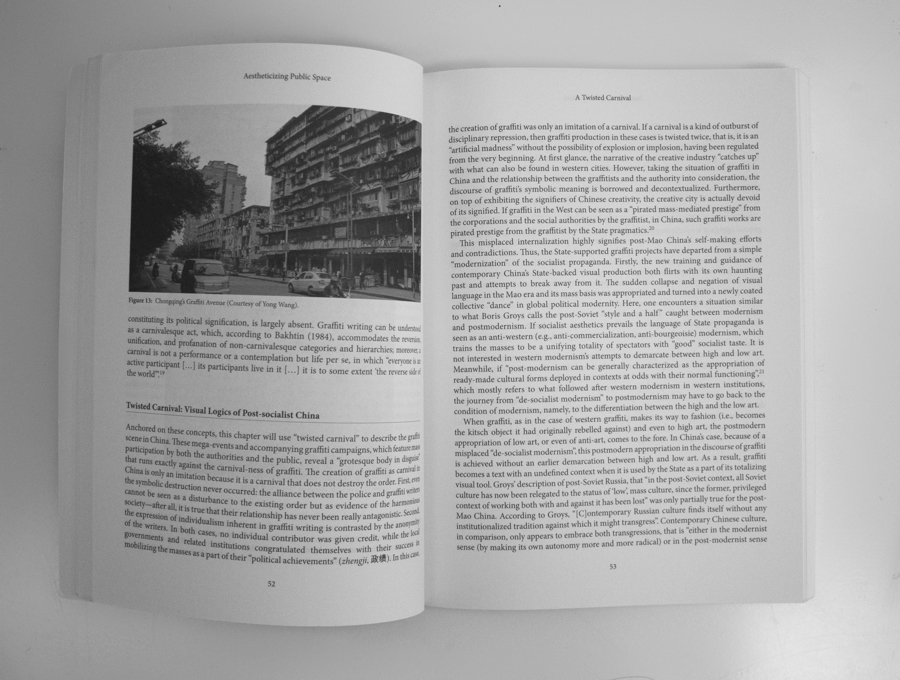

…graffiti has become a new propaganda tool for the state in China.

More generally the Chinese state has a very different approach to graffiti than you would find in the West. The government has often embraced it as a symbol of modernisation rather than decay. The emphasis on letterforms alone means that it is seen as a politically safe form of creativity. For example in chapter one Lu Pan discusses the Beijing Olympics for which a huge graffiti wall was created as a backdrop to the event. She argues that graffiti has become a new propaganda tool for the state in China. The Beijing graffiti wall attempted to project a message to the world that China is an ‘open and tolerant society’. Graffiti also had the role of mobilising “the masses to participate in State-directed events”. Similarly the government of South Korea invited graffers to paint walls in celebration of the government hosting the G-20 summit in 2010. However there is not one uniform response to graffiti across East Asia. In Hong Kong, for instance, public space is largely privatised which results in a different reaction to graff than in mainland China. The author uses the example of the ‘King of Kowloon’, who (like Helmut Seethaler in Vienna) wrote his ramblings all over the surfaces of Hong Kong, to highlight the political and cultural tensions in the city. At first his writing was dismissed as the work of a lunatic but eventually it began to gain international attention and was exhibited and sold worldwide. In Hong Kong the reaction to the King’s work has remained ambivalent; for his admirers the art is representative of something unique to Hong Kong and distinct from Chinese culture, meanwhile institutions such as the Hong Kong Museum of Art have rejected his works as peripheral. The King of Kowloon himself said he didn’t “care if they think it is art or not. I don’t think it is art, it is King’s writings”.

The reaction to the King of Kowloon also shows how not all forms of graffiti are accepted or even considered legitimate by East Asia states. Whereas in the West street-art is often seen as positive, and artists such as Banksy or Shepard Fairey have been championed because their work is regarded as ‘meaningful’ or satirical, there is often a different reaction in East Asia. In the build up to the G-20 summit, mentioned above, several promotional posters were redecorated. The artists were caught and sentenced to prison but their harsh treatment sparked a public outcry. These reactions by both the state and then the public highlight tensions within South Korea. The case can be seen as part of a wider “authoritative desire to regulate and restrain citizens” by a state that has sometimes considered the population itself as enemies of the ‘nation’. Neither the government nor the general public share a common vision of what the Korean nation is. This brings me on to one of the main themes of the book about public space and the varying definitions concerning its use.

Two other examples also demonstrate how contested use of public space can highlight the dynamic between the state and the people it rules. Lu Pan describes an incident in China where a graffiti stencil that criticised the government was quickly buffed but not before it was photographed and endlessly reproduced in cyber-space. The government’s absolute control over expression in (physical) public space meant that a small graffiti protest, that may only have been seen by hundreds of people, became an image that was seen by potentially millions across a modern form of cyber-public space. Meanwhile protests in Hong Kong, concerning its relationship to mainland China, resulted in major popular occupations of important public spaces. These occupations led to a complete change to the iconosphere of these spaces. Streets were renamed and all sorts of graffiti, stickers, wall projections, and art appeared. The spontaneous visual redefinition shows just how important the appearance of city space is in defining who controls it. Predictably the authorities eventually clamped down on the uncontrolled physical and visual participation in urban space by the public.

…the King of Kowloon is some kind of philosophical Emperor who, through his graffiti, is declaring the ‘end of history’ for Hong Kong.

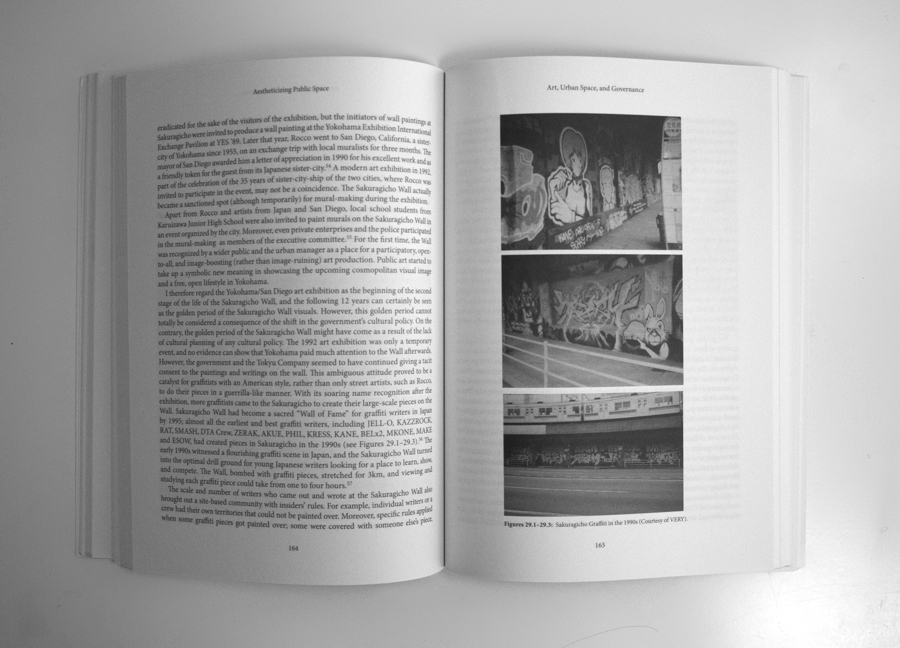

Graffiti isn’t just used by members of the public to contest ownership over public space though. It is also used by governments as a device to help reshape economies and the urban environment. As part of a huge gentrification project in Tokyo, street murals and legal graffiti walls were utilised as a visual message to attract middle-class consumers to the area. In another gentrification drive, this time in Yokohama, the Sakuragicho free-wall was co-opted by the authorities. It was reproduced as a sanitised permission wall which included having adverts for businesses painted on it. Lu Pan uses the case of AGIT, an alternative community space, to criticise state planning and top-down policies. She argues that urban planning projects have led to increased alienation, surveillance, policing, and the creation of “pseudo public spaces” with a focus on consumerism. Although at times she presents an oddly uncritical examination of neoliberalism and state planning. Lu Pan is enthusiastic about the gentrification project in Yokohama which swept away the culture rich downtown to replace it with skyscrapers and arts centres. Another Japanese project she discusses is the ‘Tokyo Wonder Site’. This is a government arts organisation formed to promote a ‘creative economy’. In some sort of neoliberal doublespeak Lu Pan says the TWS recognises “the importance of bottom-up community-based sites of Asian creative production and circulation.” One project in the city that apparently involved the community, in this case landlords and businesses, had the ‘positive’ result of removing graffiti and the homeless – presumably to an as yet un-gentrified area of the city instead. Ultimately the author says that graffiti “should not be encouraged” although she believes that definitions of public art and space are often arbitrary and simplistic.

Through these cases Lu Pan demonstrates how invasive globalisation is and, in context, just how complex graffiti can be. To do this, in each chapter she interprets the subject using different philosophical theories. For instance when she’s discussing protest graffiti in China she uses the ideas of Walter Benjamin. I found this a bit dense but the gist was that through sheer repetition the graffiti was absorbed by the ‘masses’ and effectively challenged the dominance of official propaganda. However in other parts of the book I just couldn’t get to grips with the philosophy. Lu Pan starts early on by mentioning Jean Baudrillard (he seems to crop up in most academic works on graffiti) who wrote that the ‘meaninglessness’ of graffiti is what gives it visual power. His argument seems to contradict the author’s though as throughout the book she shows that graffiti is meaningful and this meaning is drawn from its context. While Braudrillard said that graffiti writers “care little for architecture; they defile it, forget about it”, Lu Pan uses examples of work by the street-artist JR to show the exact opposite. In chapter two Lu Pan introduces the concept of the ‘End of History’. This term was originally coined by the French philosopher Kojève and built on by Fukuyama. The concept basically argues that neoliberalism is the perfect state of existence for mankind and, as the world falls into line, a new static and complacent Man is created. Lu Pan draws on this to conclude that the King of Kowloon is some kind of philosophical Emperor who, through his graffiti, is declaring the ‘end of history’ for Hong Kong. Kojèves theory comes across as intellectual waffle and doesn’t add much to understanding how graffiti relates to the cultural and political forces affecting Hong Kong. Elsewhere Bakhtin’s interesting idea of the ‘carnivalesque’ is brought in to discuss the use of graffiti at the 2008 Olympic games but here I just got bogged down in the academic language of postmodernism, (post)modernism, de-socialist modernism and all the other variants. In fact I struggled with a lot of the philosophical stuff within the book. To what extent that’s due to my ignorance of the subject, and how much is down to academic opaqueness, I can’t say.

Throughout Aestheticizing Public Space there is incisive analysis and Lu Pan effectively tackles complicated topics through graffiti. There is an open minded treatment of the subject including interviews with graffiti artists whose views are treated as serious parts of the debate. Lu Pan is particularly good at setting graffiti within its specific Asian context. She is ambitious in discussing the history, politics and culture of the region while showing just how complex any interpretation of graffiti can be. Some parts of the text are hard going but overall it is a really interesting and informative publication. This book is an example of how to go about studying graffiti and, because of its analysis and exploration of wider ideas through graffiti, is up there as one of the better academic works I’ve read on the subject.

Pingback: Framing A Counter-Narrative – Graffiti Review